2020

My Back Pages Thirty Years Ago In Guitar Player (February 1990)

Click here to see all of the previous posts!

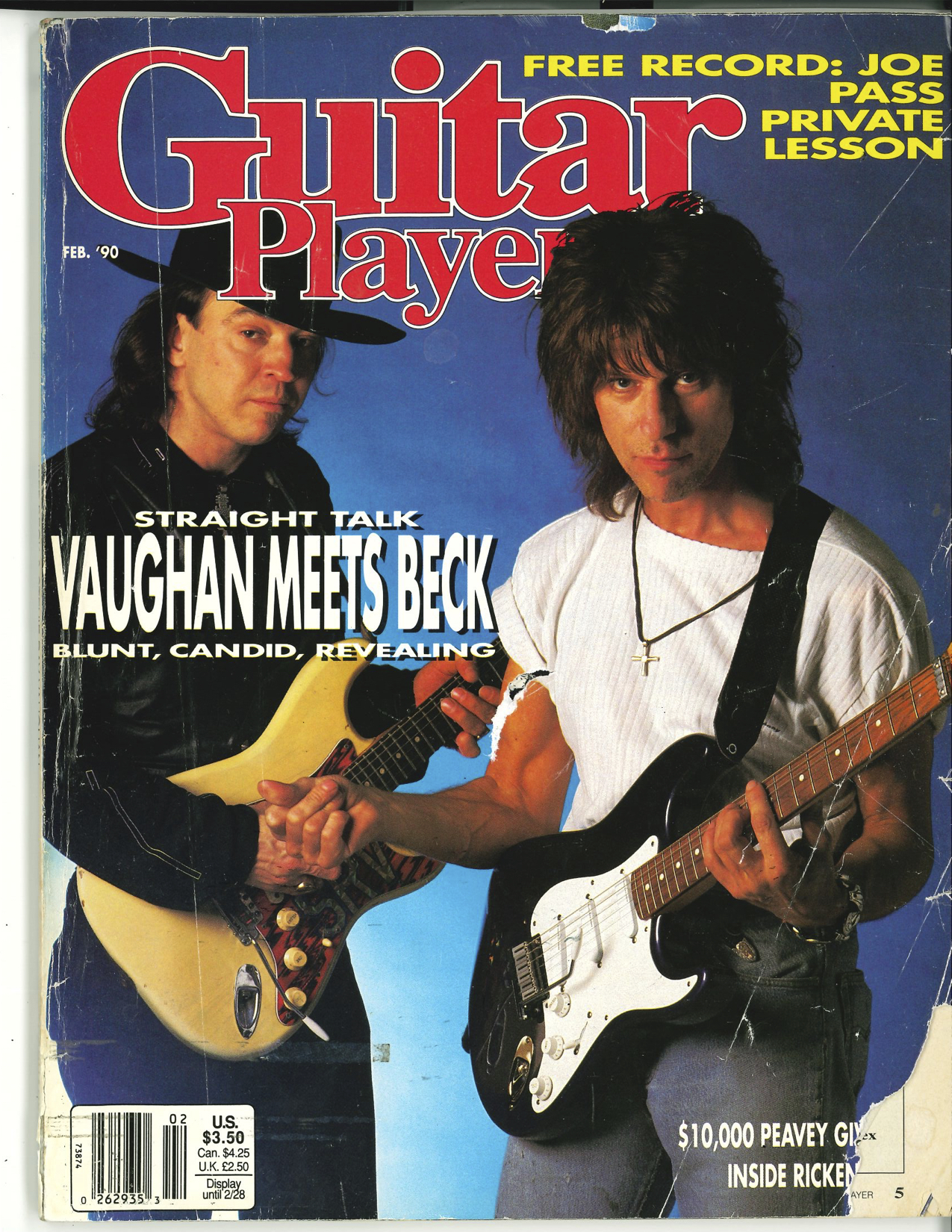

The February, 1990 issue of Guitar Player was an incredibly important magazine for me, because it is what ultimately led me to buy my Stratocaster. I had been playing an Epiphone Sheraton, which was a cool guitar, but mine had all kinds of tuning issues, plus it was big and bulky. I’d been a fan of Clapton and SRV for years, and after reading this issue I decided to get a Strat. I didn’t have the money saved until July (and I had to trade the Epiphone and an acoustic as well), but I remember after reading this that I asked my parents to send me the August, 1987 “Strat Mania” issue (which was in my bedroom back in Pennsylvania) so that I could learn all I could about Stratocasters.

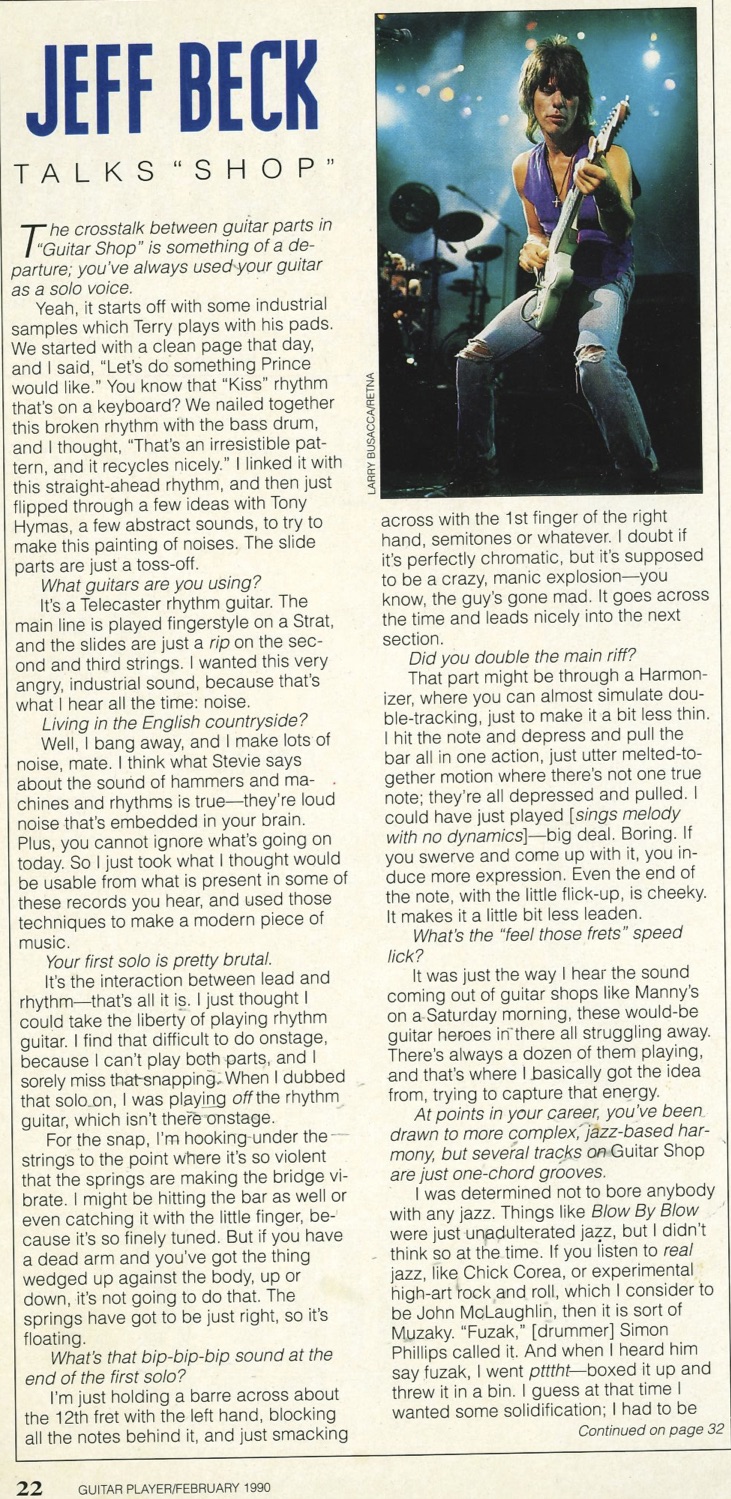

This issue also makes me a little wistful. I remember that the Jeff Beck/Stevie Ray Vaughan double headline tour came pretty near to where I was in college, but I just thought “I’ll have plenty of time to see them again”, and declined a friend’s offer of tickets. The tour was over by the time this issue came out, and the articles gave me the sneaking suspicion that I had made a big mistake. Of course, we all know that SRV perished in a helicopter accident later that summer, so I never got to see him in person. I DID eventually see Jeff Beck in 2009, and it was amazing, but I’ll always wish that I had caught their show in Worcester in the fall of 1989.

While there is some other good stuff in this issue, this month’s blog post will focus on the JB/SRV content. There was a joint interview, separate interviews, and a feature where guitar repairman Dan Erlewine detailed the setup of Beck’s and Vaughan’s guitars. In other words, lots of good stuff!

*****************

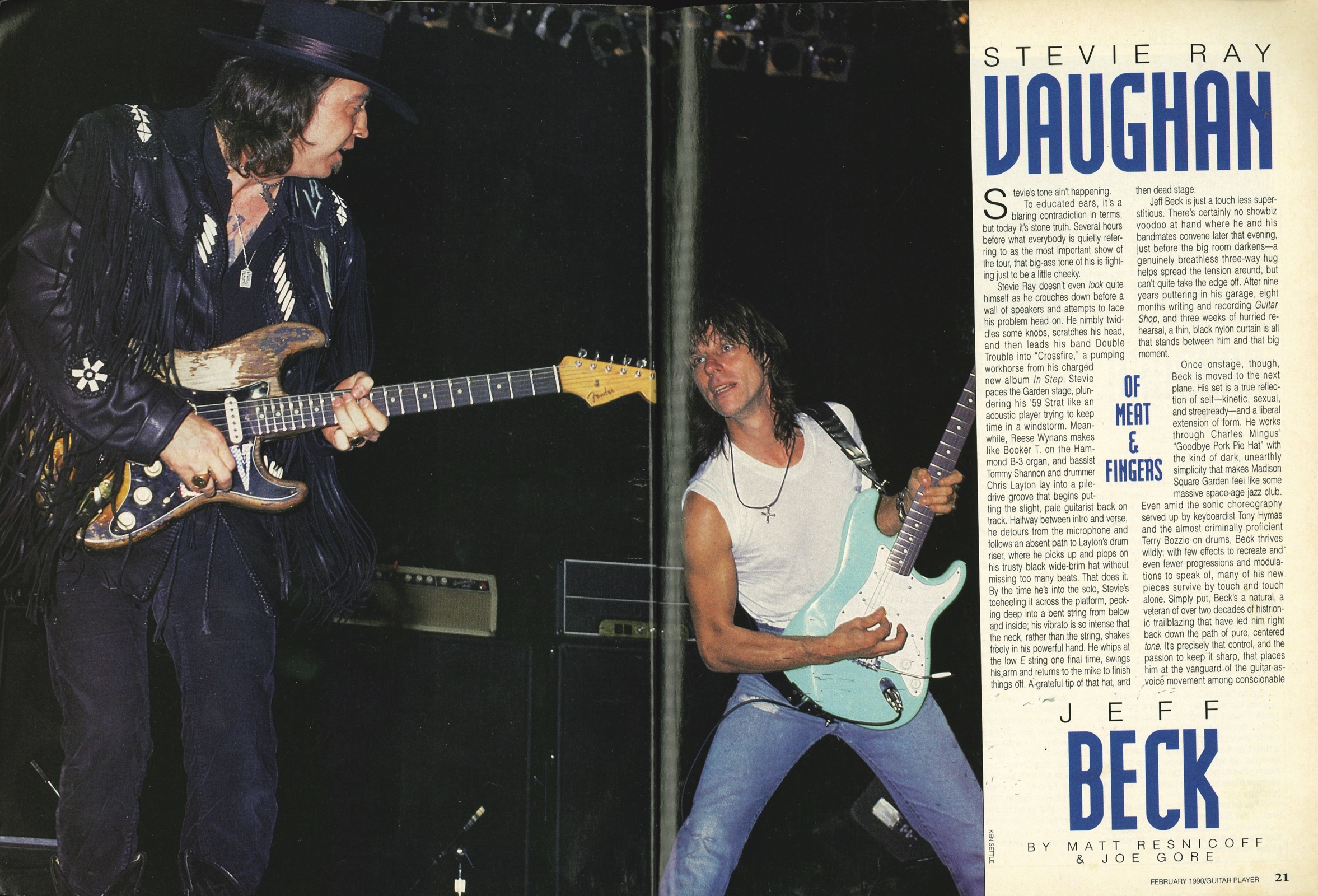

The dual interview by Matt Resnicoff and Joe Gore touches on some cool points about the blues, the state of music at the dawn of a new decade, and guitar playing in general. Here are some excerpts:

Both of your styles are grounded firmly in blues tradition, but you each take that tradition in very different directions.

SRV: I play it less original than most people I’ve heard. This is one of the things that blows my mind about what Jeff does, that he takes the roots of it and is able to make it go way out there. That’s what Buddy Guy did, Hubert Sumlin, Muddy Waters. They all changed it up and did their own thing with it.

JB: But I wasn’t even close to it. I was three and a half thousand miles away in suburban England, and all I had was this fuzzy radio to listen to, and I’d read things and try to steal records when no one’s looking. I used to go and listen for hours and wear all the records out and then just buy one. Befriend your local record-store guy–that was the way to do it. That was a big awakening for me. And going to art school was great because we’d just lend each other records and drink. That’s all we could do.

Is there a way of recapturing that essence [of 50’s blues and rockabilly]?

JB: [Sighs] That’s a tough one. Part of the reason I’m sitting here is because I believe in real music. A drummer like Terry Bozzio and a keyboardist like Tony Hymas can go any route you want, but still enjoy the performance and interaction of playing real music. That’s what I’m here to say. If you’re a kid locked up in a bedroom with loads of high-tech stuff–that’s not the way it is, and you shouldn’t be pinned down to it just because the record industry has made it like that….I hope the ’90s will eliminate a bit of that corporate pushbutton music, which I just loathe.

SRV: There are people who still like to play. I personally wouldn’t know how to play with a bunch of machines. When I was learning to play off of records, I might be able to play right along with it, but then I’d go out and try to play with somebody, and I couldn’t. I had to learn. It’s the same thing in a lot of ways.

JB: You’re locking into a person’s groove, and you understand fully that groove. You understand the slight error of timing, and that is the glory of it all, the joy of it.

SRV: A song needs to breathe. The rhythm needs to breathe. Sometimes the best way to get some punch out of something is to slow down right before you hit it it. Kind of like a slingshot-pow!

Jeff, what was it like to jam with Hendrix?

SRV: Yeah, good question.

JB: What was it like? Well [pause], it was awful! The first time, I felt like a peanut, like a fucking hole would have opened up and swallowed me. The thing that puts it right is the fact that there’s a genuine love that Jimi had for my style as well, which couldn’t believe. Then I realized that Jimi was not a messiah; he was a very genuine, dyed-in-the-wool, music-loving person. He didn’t give a damn about the reputation, the show biz razzmatazz. All he was interested in were the licks and what you were feeling like–kind of like Buddy Guy. Remember that night we were playing with Buddy? It was a conversation. The guitar was just talking and he was listening and looking: “Hmm, that’s interesting!”

It was much the same with Jimi. He wasn’t out to blow you off the stage at all. If he did, he did, but…What am I talking about, ‘if’? Phew. It was great. When I got friendly with him, it was just sadness that we couldn’t nurture the friendship a bit more. In those days, life was just totally crazy. He would be off in a 24-hours-a-day lifestyle, and I couldn’t keep up with it. I had to have my sleep. He was a boogier–a club here, club there, and he’d be jamming until 5:00 in the morning. My lifestyle was never destined to be like that, so I just had to say, “Adios, Jim, I gotta go to bed!” I felt very amateurish alongside him, because he lived and breathed it. You’re very similar to Jimi in that way. I’m just a part time employee.

SRV: I don’t know about that one [laughs].

JB: I’m not in love with the guitar as much as you are or Jimi is–was. I just pick it up and play sometimes. I feel really guilty. Whatever I choose to do, it always robs me of something. The guitar robs me of my time building [hot] rods, and the rods take their toll on the playing. But the payoff is the refreshment on both sides. By building, I’m able to completely steep myself in physical things, and all the time I’m doing that, I’m thinking of licks and music, which I’m not able to do sitting with a guitar. That’s probably the reason I’m able to maintain a modicum of interest in music after 30-odd years.

The Strat requires a lot of hand strength. And you both use fairly macho action on top of that.

JB: That’s part of the reason I started playing it onstage, because I found that the energy level was 50 times more than sitting around at home. And it’s better to have something that’s tuned up for that, rather than sloppy action that makes you say “Oh God! I wish it was harder to play. This is too easy!” Then you start sliding downhill. You have to have this thing just above you, pulling you, making you work.

SRV: If I put smaller strings on there so they don’t hurt, I can’t get the same sound. Then my tendency is to play harder, and I just tear things off. Sometimes at home I either tune down to C and leave the same strings on, or I put lighter strings on and use a light pick so I start remembering about a lighter touch. But when I get on stage, I really need the big strings.

Good stuff. The rest of the interview is fine, but not much jumps out, except the poignancy of Vaughan discussing the kind of things he expected to do in the future. On the tour, they were “double headliners”, and only played together for a single encore, of “Going Down”. Here is a clip from one of the first dates of the tour:

*****************

There are some good highlights in the separate interviews, where the guitarists talk about their recent records Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop and In Step, by Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble.

The interview with Beck has a lot of good stuff when he is reflecting on his career and his influences. Here are some notable excerpts:

The interview with Beck has a lot of good stuff when he is reflecting on his career and his influences. Here are some notable excerpts:

At points in your career, you’ve been drawn to more complex, jazz-based harmony, but several tracks on Guitar Shop are just one-chord grooves.

I was determined not to bore anybody with any jazz. Things like Blow By Blow were just unadulterated jazz, but I didn’t think so at the time. If you listen to real jazz, like Chick Corea, or experimental high-art rock and roll, which I consider to be John McLaughlin, then it is sort of Muzaky. “Fuzak” Simon Phillips called it. And when I heard him say fuzak, I went phttht–boxed it up and threw it in a bin. I guess at that time I wanted some solidification; I had to be playing a tune, not just abstract flurries of noise. There had to be some nice chords to get the listener to draw an ear a bit closer.

But I shouldn’t have done Blow By Blow. I wish I hadn’t done any of them, because they’re just mistakes on record. I wish I had stayed with earthy rock and roll. I got sucked into….When you’re surrounded with very musical people like Max Middleton and Clive Chaman, you’re in a prison, and you have to play along with that. I wasn’t able to direct them against their grain, so that’s what came out.

Do you dislike being perceived as a fusion player because you don’t feel you really are one, or because you don’t like the implication the label carries?

It’s a bad word now.

But at the time, it meant a bringing together of musical worlds, and in many ways still does.

Yeah, well that’s not necessarily a good thing. It’s like taking a bit of vanilla ice cream and pouring something else over it to cover up the vanilla. You either like vanilla or you don’t. I mean, you can make it better with chocolate sauce, but it’s not right when you try to put another flavor in. It’s like lime in your Perrier. I mean, Perrier is Perrier. You’ve got to look for the single elements sometimes.

But the same can be said about the marriage of blues and rock.

Yeah. Well, there are some good things on Blow By Blow. It just reminds me of flared trousers and double-breasted jackets. I didn’t like the ’60s and ’70s basically. I hated them. The mid ’60s were okay, because every day was a hurricane in the Yardbirds and I could afford to look at it with contempt; around me were a lot of things I had nothing to do with, like flower power and awful things like flared trousers.

Were there things about the ’80s you felt more drawn to?

I did, because of the revitalizing of things, like punk rock, which I loved and thought was a smack in the eye for the world. It made things a lot more exciting and insecure. It was getting very stodgy. I was getting so depressed by ’65 because I was 10 years too late to be around the Gene Vincent, Cliff Gallup thing, and I bitterly resent that. …

Did you ever meet Cliff Gallup?

He’s the biggest unsung hero of all time, and then he goes and dies. No. He didn’t know I existed. The awe I would have been in of him, and he would have been sitting there, wishing he was fishing. I would have just liked to hear one syllable. His voice would have satisfied me: “Fuck off” or something. I never even got that, unfortunately.

No doubt about it, Jeff Beck comes off as a unique, perhaps difficult guy, but I have always admired his approach to music. Beck is always looking forward, and trying to improve. I find that to be a fascinating contrast to his boyhood friend Jimmy Page, who seemingly hasn’t created new music for decades, and just loses himself in repeated remastering of old Led Zeppelin recordings. I’m not saying I think one approach is better; the world is lucky to have both Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. But there is a real contrast.

*****************

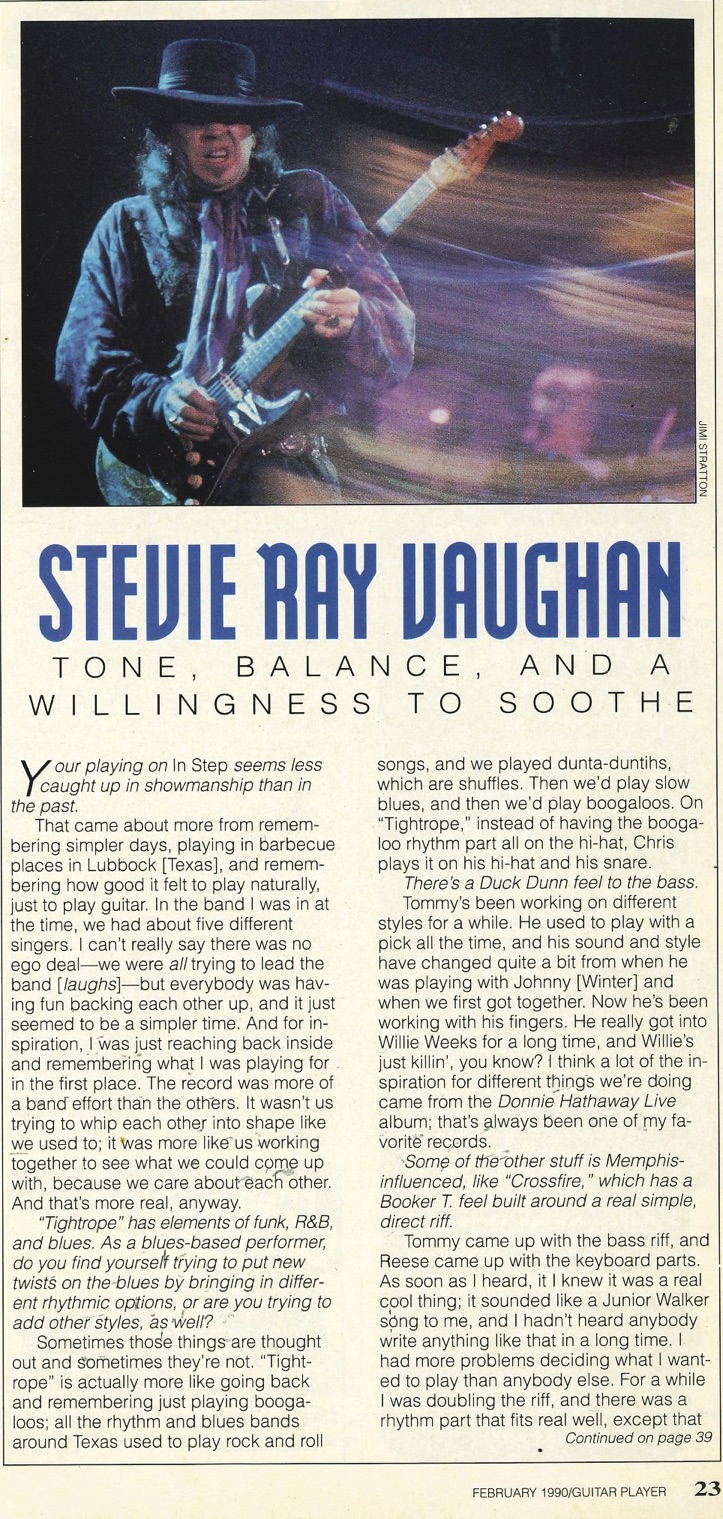

The interview with SRV is mostly focused on the In Step album and his gear. By now, most of the lore of Stevie Ray’s gear is well-known, but I thought I’d share a couple excerpts about his strings and his sobriety:

The interview with SRV is mostly focused on the In Step album and his gear. By now, most of the lore of Stevie Ray’s gear is well-known, but I thought I’d share a couple excerpts about his strings and his sobriety:

You’re using pretty tough strings.

I’m using a lighter setup now because I’ve got a hole in my finger. Because of the schedule we’ve had, Rene [Martinez] hasn’t had the chance to dress the very edges of my frets, and I just found yesterday that at the points where I play a lot, my calluses were getting ripped off to where it stuck a hole in the finger. Right now I’m using a little bit lighter strings, just until I get my calluses back.

Then you’re going back to an .013 E?

Yeah. I like the sound of them, I really do, even though it’s painful to use them. I used to use a lot heavier. I used to use an .018.

On the E string ?!

Yeah. In a way, it was insane, but I played a lot more simply, and what I chose to play was very to the point. I got out of that, and into using smaller strings just looking for recognition, I guess, looking for flash. But using bigger strings and playing slower was my way of being able to be reserved. Of course, I couldn’t see playing as many gigs as we’re doing now like that; I don’t think my hands would hold up. They’re not holding up right now.

What did you have on the bottom, a .127?

[Laughs]. The biggest one I found so far was a .074. It’s been years and years since I found them, and I just used them for a little bit, because they ate tuning heads, but it was great. You’d hit an open E and it sounded like “Crosstown Traffic”, that piano part. Those things are fun, and I like that sound, but then again I don’t think there are many amps that can take that for very long. Right now I’m using .058s through .012’s.

Are you involved in a 12-Step Rehabilitation Program?

Three years and one month. I wouldn’t be alive without it.

Why would a person in such a fortunate position become an addict?

I got started a long time ago. I was probably born an alcoholic and an addict. A lot of us are; it’s hereditary. Becoming a compulsive of any kind is a genetic thing, and it’s very easy to develop a disease of addiction if you don’t know when to stop or if you’re trying to keep up with or impress somebody. It’s the rock and roll myth; let’s face it, it’s everywhere. “It’s cool to get high. If you’re higher than somebody, you must be cooler.” The same old bullshit. And I believed it. I grew up in the ’60s when that’s what everybody did. For the first few years, I didn’t really feel better, but I thought I was supposed to, and I thought I was more accepted if I did, so I floored it. And the more caught up in it I got, the more I started to believe it.

By the early ’70s or so, I didn’t know how to do anything without it. Without the crutch. I didn’t feel like I had the stamina or the coolness. The further we went, the more stressful it got, the more I thought I had to deliver, and the more I believed that I got from dope and drinking. The real trap is, the more a person pulls off, there’s no reason why a manager won’t say, “Oh, if he can do that, let’s do this one, and this one.” It got to where we were doing schedules nobody could do, and I wouldn’t have enough right thinking going on to make it known that I didn’t feel good about it. I would stuff those feelings, get mad, then say “Well, I guess that means I better do some more drugs.” It got to where if I was awake, I was snorting something, or guzzling something, and it got to where if I had to get up in a few hours, that was my excuse not to go to bed. It’s a sickness.

Is it getting easier?

Some. A few more brain cells are kicking in. That’s something else that’s funny–actually, it’s not necessarily all that funny. Some of the damage that was done during all the abuse time really pisses me off, because I didn’t realize what I was doing. I didn’t realize….Then it was a joke, “Here goes a few more brain cells.” And everybody laughs. But it really makes me mad when I consider all the damage I did. And the weird thing is, had I known what I was doing, I don’t know whether that would have been enough to stop me. Because it took really hitting the bottom to give up the fight. “Riviera Paradise” is a product of coming back. That’s one thing that stayed constant: that song was always meant to soothe–to soothe feelings, and especially pain. And that’s the same thing the song “Lenny” was written for. I guess that’s what music’s really for in the first place, whether it excites you, makes you go through something, painful or not. The end result should still soothe in some way.

I was devastated when Stevie Ray Vaughan died, and I didn’t get over it for a long time. I loved his music, but the thing that hurt the most was that he had just got his life together and was moving forward clean and sober with such a bright future ahead of him.

*****************

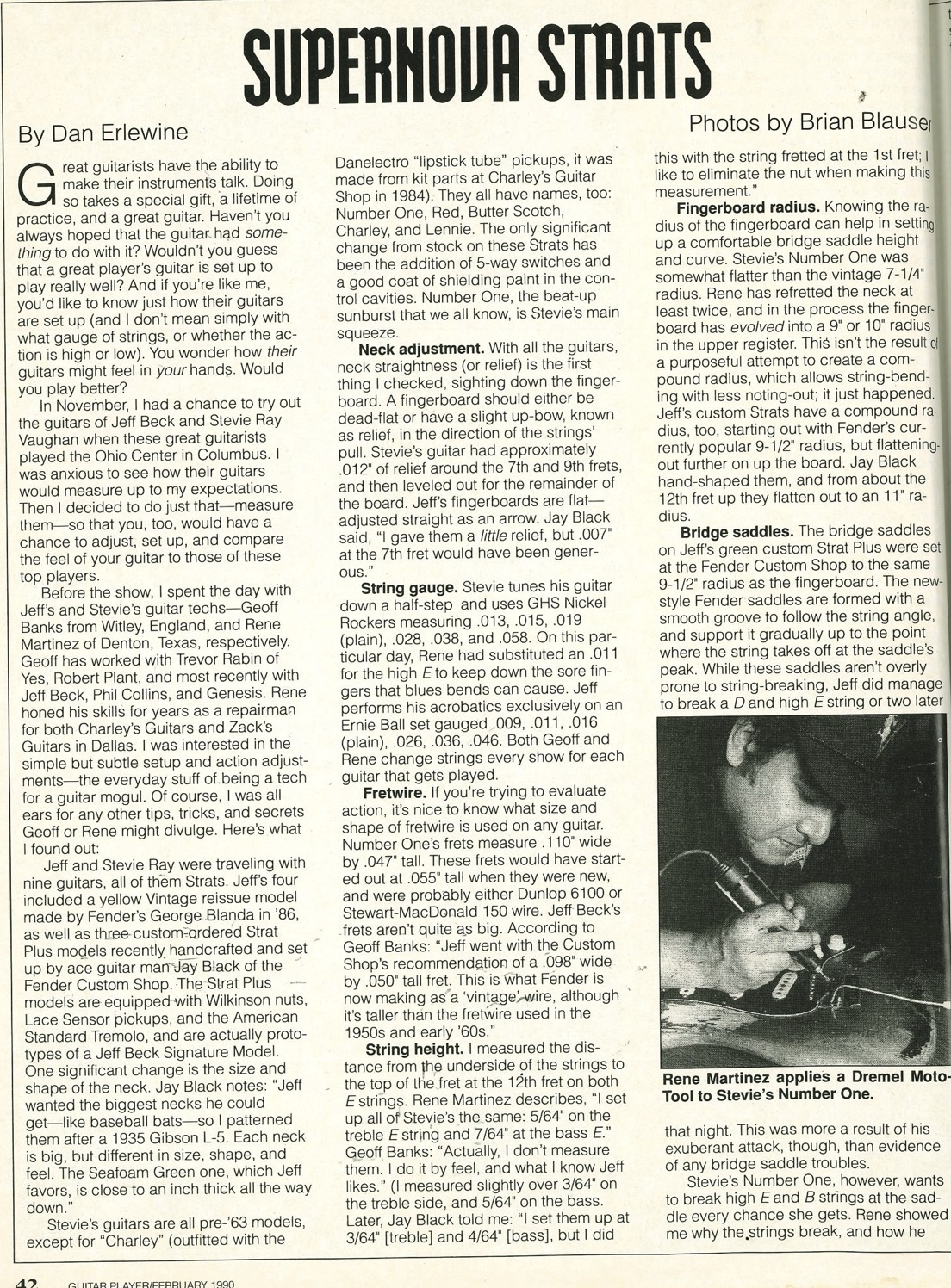

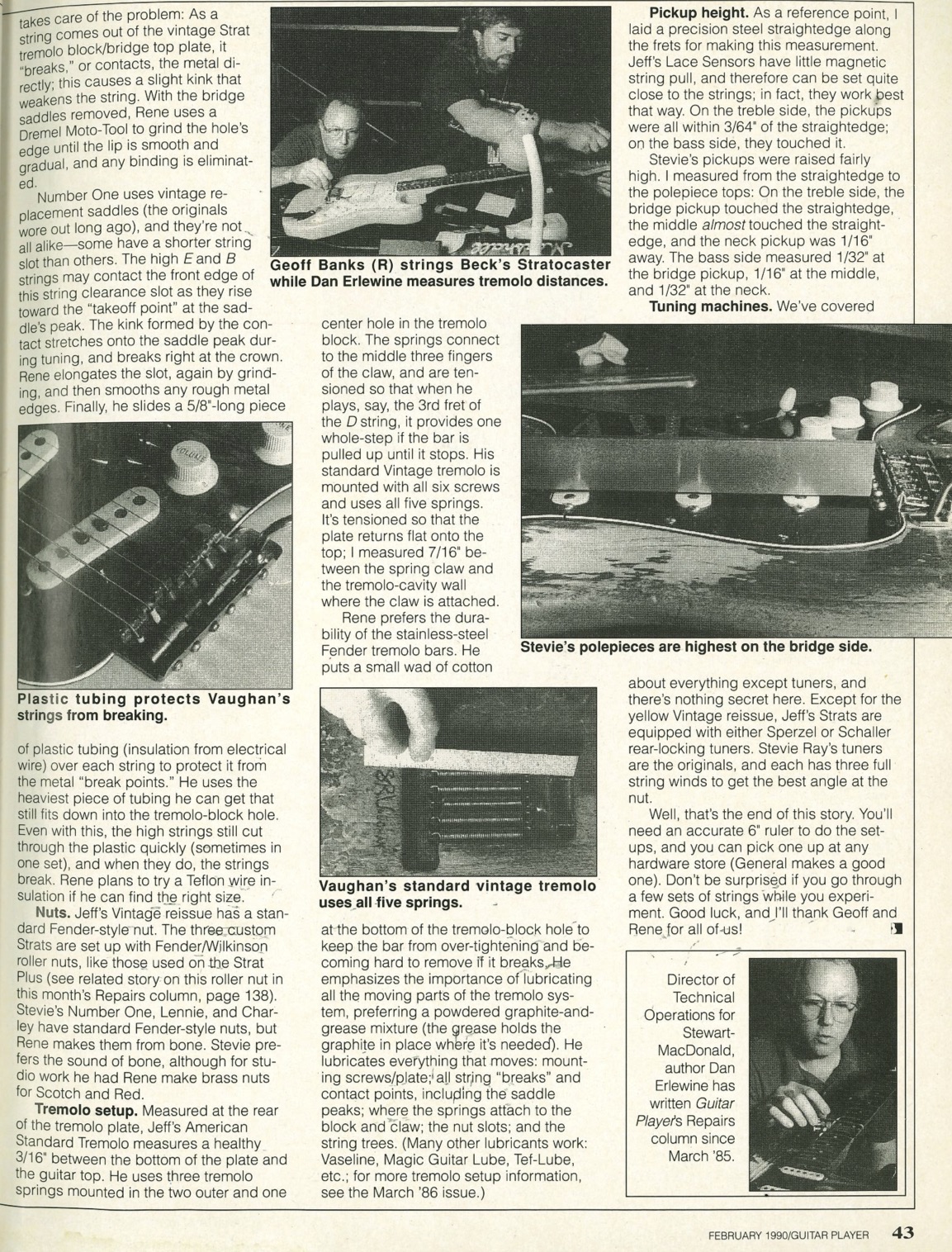

The Dan Erlewine section where he does a close look at the setups of Stevie Ray’s and Jeff’s Stratocasters is pretty cool, so here are the pages for you to see:

*****************

That’s it for now. This month’s playlist lacks variety, but it does have a Muddy Waters Chess records box set, so it’s not too bad! I’ll see you in March for a good issue with Alan Holdsworth on the cover. Until then, keep on picking!

*****************

Hits: 695