2018

My Back Pages: Thirty Years Ago in Guitar Player (March 1988)

Welcome back to “30 Years Ago”, where I take a close look at the issue of Guitar Player magazine from exactly thirty years prior to discuss what I gleaned from the issue at the time and what I can learn from re-reading so many decades later. I also provide a Spotify playlist that includes music that was mentioned in the month’s issue. Click here to see all of the previous posts!

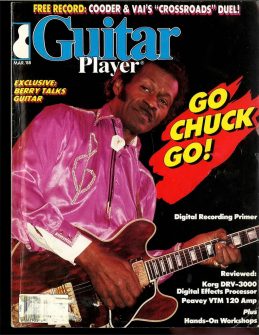

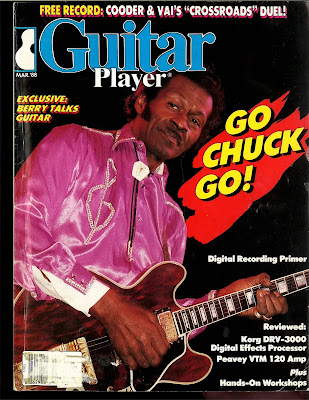

In March of 1988 I was playing my new Epiphone Sheraton II along with my Peavey T-15 and newly acquired Fender Avalon acoustic, taking lessons with my GIT-trained teacher Jim McCarthy, and continuing to swim in a blend of music, from jazz on radio station WRTI, classic rock on stations WMMR and WYSP, pop and metal on MTV, country on The Nashville Network and Austin City Limits, and blues on a local radio station whose call sign I forget. The varied content in the March 1988 Guitar Player, featuring as it did articles on Chuck Berry, bebopper Rory Stuart, blues/world music/composer for movies star Ry Cooder, country bassist Emory Gordy Jr., and western swing legend Eldon Shamblin definitely would have appealed to my wide-ranging musical interests.

I remember this issue pretty well; in fact I have a very clear memory of bringing it to school with me and reading it there. Re-reading it makes it clear that nearly EVERYTHING I know about Chuck Berry came from this issue; it is probably where I learned about western swing (though I know that I had at least one Asleep at the Wheel record, so that might not be totally the case). I know that this might be one of the first issues that I kept re-reading (mostly for the Chuck Berry parts– all of which are heavily underlined, starred and otherwise marked up by yours truly) and remember taking it to one of my lessons. That day I showed the Berry article to my teacher, who pulled out several mimeographed basic rock lessons from GIT and gave them to me to study (they are still in my music folder to this day, very well thumbed).

I remember this issue pretty well; in fact I have a very clear memory of bringing it to school with me and reading it there. Re-reading it makes it clear that nearly EVERYTHING I know about Chuck Berry came from this issue; it is probably where I learned about western swing (though I know that I had at least one Asleep at the Wheel record, so that might not be totally the case). I know that this might be one of the first issues that I kept re-reading (mostly for the Chuck Berry parts– all of which are heavily underlined, starred and otherwise marked up by yours truly) and remember taking it to one of my lessons. That day I showed the Berry article to my teacher, who pulled out several mimeographed basic rock lessons from GIT and gave them to me to study (they are still in my music folder to this day, very well thumbed).

In 1988 Chuck Berry was 62 years old, only three decades removed from the prime of his career (hard to imagine that!) and coming off a mini-renaissance highlighted by the publication of an autobiography and the movie “Hail Hail Rock n Roll“, where Keith Richards put together an all-star band (including Chuck’s piano collaborator from the ’50’s Jonnie Johnson) to give Berry a chance to play with competent musicians, as opposed to the local pickup groups specified in his contract riders. Of course with Berry’s death last March (29 years after this article) it feels even more appropriate to learn more about the father of rock guitar.

The late Tom Wheeler wrote the feature based on his interviews of Berry, and it is a really terrific piece of writing:

“Chuck Berry came motorvatin’ over the hill in the summer of ’55, his Gibson ES-350T blaring and clanging like Maybellene’s roadhog Coupe de Ville. It was one of the most compelling and enduring images in pop culture: the loose-jointed, duck-walking hipster with the low-slung guitar, the happening threads, the wicked gleam in his eye….

Early rock’s foremost singer/songwriter, Chuck wrote classic two-and-a-half-minute novellas of churning hormones and rock fever. In Berry’s America, street-savvy hepcats tooled around in cherry-red jitneys and coffee-colored Cadillacs, chasing after sweet little rock and rollers such as Nadine, who moved around like a wayward summer breeze, or Little Queenie, lookin’ like a model on the cover of a magazine. A percussionist of sorts who used syllables instead of drumsticks, he fashioned his lyrics into a sly, jivey poetry that percolated with its own gimme five lingo: motorvatin’, coolerator, botheration—and pulsed with irresistible rhythms….

And even if his writing, singing and stylistic alchemy had not already secured him a place on rock’s Mount Rushmore, Chuck Berry would be celebrated today for his guitar playing alone. His style was innovative in its sound and technique, and its ringin’-a-bell tone, jolting syncopations, slippery bends and whole new vocabulary of double-stops simply changed the way the instrument is played…

At 61, Chuck Berry is a formidable presence, his lean body still moving with the grace of an athlete, his eyes still twinkling with the mischief of a rakish Hollywood leading man. He is at once a tough hombre and a gracious gentleman, obsessively private one moment, expansive and personable the next. Traveling alone and using pick-up musicians who are often under-rehearsed, he is self-contained: singer, songwriter, guitar player, legend…

A few years ago, US spacecraft Voyager was blasted into deep space, past Jupiter and Saturn and on towards Neptune, four billion miles from St. Louis, Missouri. On board are recorded greetings to anyone who might encounter it. Among the messages representing planet Earth is a recording of “Johnny B. Goode”, lending new meaning to the phrase “long live rock and roll”. Maybe some day countless millennia from now, across the universe, some unimaginable alien thing will be snapping its fingers (or whatever) and grooving on the ancient tale of the country boy that could play his guitar just like ringin’ a bell.

Good stuff! The interview was quite interesting, especially as it helps one to understand the mindset of a struggling musician, nearing 30 years old and frustrated by his day job as a hairdresser who did whatever he could to become a success. And of course the racial issues faced by a black musician who became popular with white teenagers are never far from the surface. I know that when I first read the interview I was most focused on learning about guitar technique and Berry’s influences, but re-reading it, I am struck by more “social history” parts of the interview:

Q. Do you see two distinct sides to your music, the rock and the blues?

A. Well, things like “Johnny B. Goode” and “Carol”, those were for the mass market. “Wee Wee Hours”, that was for the neighborhood. But this isn’t a black/white thing. That irks me. There’s no such thing as black and white in music.

Q. In May ’55 you were doing some carpentry and studying cosmetology; three months later your first record was #5 in the Hot 100 and #1 on the R&B chart. How did the almost literal overnight success change your life?

A. The only thing it changed was my determination to follow through as long as it could go.. My lifestyle did not change one bit. I had been saving 80% of my income as a carpenter, and saved 80% of my income as a musician.

Q. Was fame what you had expected?

A. No, because I didn’t expect it! I was making $21 a week at the Cosmo, and it went to $800 a week after “Maybellene”. I didn’t give a shit about the fame, and you can print that! Still don’t. The only thing I cared about was being able to walk into a restaurant and get served, and that was something I should have had anyway, without all the fame. See this was 1955, and [civil rights] marching and things were about to start. I liked the idea that I could buy something on credit and the salesman knew I could really pay for it. I could call a hotel and the wouldn’t automatically offer me the economy rooms after hearing how my voice sounded. That I admired.

For all the social history, there is a lot of music and guitar detail in the Berry feature, which spreads over 17 pages of the magazine. The section “Chuck Berry, the records”, breaks down guitar highlights from 20 of Berry’s classics. For “Carol” (my personal favorite Chuck tune), they promise “next month, Guitar Player will present an in-depth article, with transcription, exploring the intricacies” of the song. Unfortunately, that promised article never materialized, and I’ve always wondered why. There’s also several good pictures of Chuck’s guitars including the bit of proto-gear porn below:

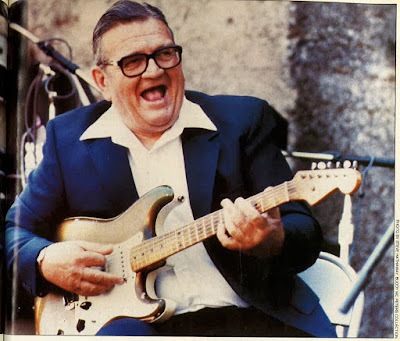

Another guitar legend who helped create the vocabulary for an entire genre was Eldon Shamblin, who played lead guitar for Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. The profile of the then 72-year old was very informative. I learned a lot about Texas swing and other music that I enjoyed when it would be on TV’s Nashville Network or (more rarely) on a radio show. Gear wise, dig the guitar Eldon is playing: a gold-finished 1954 Stratocaster with chicken-head knobs given to him by Leo Fender himself. According to the article the Texas Playboys were used by Fender to road test his early equipment. In 1954 while visiting the factory,

“Leo said, ‘Hey-we’re coming out with something. Why don’t you take this? Just it and try it. If you don’t like it, you can bring it back.’ I found I liked it…I’ve tried other Fenders but I can’t find one that compares to this one for rhythm. I have never found one like this. I read in Guitar Player that mine was the first metallic color Fender ever put out. Everything is original–controls, frets, pickups, everything.”

Pretty cool! Also neat was to read that he blocked off the tremolo and used heavy strings, two things that I eventually did with my own Strat (a metallic pewter colored ax) when I got it in 1990, but that’s a story for another day.

The article with Ry Cooder was interesting to me for a lot of reasons. First of all, as a young blues fanatic, the movie Crossroads –where Karate Kid Ralph Macchio basically recreates that movie in a blues guitar context (young classical guitarist Eugene secretly loves the blues and Robert Johnson; he helps Willie Brown break out of an old-folks home and they go down south to the crossroads in Mississippi where Eugene battles the devil’s guitarist, played by Steve Vai, for Brown’s soul) was a favorite of mine, one that I saw twice in theatres and several more times on cable. It’s simultaneously terrible and amazing! Even at the time I was uncomfortable with how Eugene wins the head cutting contest by replacing the blues with Paganini, but it’s still a cool scene:

I know that the showdown between Vai and Macchio is still frequently discussed on internet guitar forums, so here is Ry Cooder’s description of how the scene came to be. It’s a neat glimpse behind the scenes:

Hits: 237