2017

My Back Pages: Thirty Years Ago in Guitar Player Magazine (August 1987)

Welcome back to “30 Years Ago”, where I take a close look at the issue of Guitar Player magazine from exactly thirty years prior to discuss what I gleaned from the issue at the time and what I can learn from rereading so many decades later. I also provide a Spotify playlist that includes music that was mentioned in the month’s issue.

This installment is a little late because my wife and I recently moved, for the 10th time in 24 years. That means that I’ve schlepped my Guitar Player issues with me all over the country for decades. This month’s issue, in fact, has actually been with me in a dozen places–it was originally sent to the home I grew up in, then I asked my parents to send it to me in college a few years later, and I’ve had it ever since. Pretty cool to think how important these old magazines are to me!

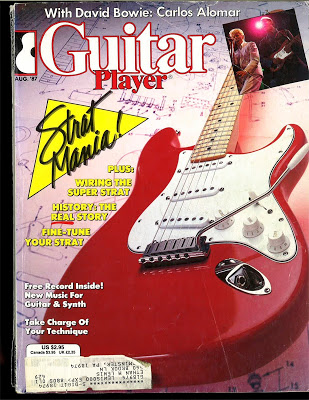

While I couldn’t have known it when it arrived, the August, 1987 issue of Guitar Player went on to become highly significant to me in several ways. In the coming years, I bought two electric guitars (you’ll be able to read all about them when the time comes): a 1987 Epiphone Sheraton II (which I sold in 1990) and a 1989 Fender Stratocaster that I still have (funded, in part, by the sale of the Epiphone). This issue of GP contains a nice article about the history of the Sheraton, and the cover article and other features made for 20 pages of information about Strats that I read and re-read in 1990 before buying mine.

Looking back at the issue today, it is full of other interesting features, including really great articles on Chicago bluesman Jimmy Rogers, bebop phenom and Merle Haggard sideman Clint Strong, and tributes to late guitar giants Freddie Green and Andres Segovia. There’s also nice articles with Robert Cray’s bassist Richard Cousins and David Bowie’s sideman Carlos Alomar discussing his new synth-based solo album.

The magazine started off with a very nice feature about “Tonight Show” guitarist Bob Bain in the opening pages. Bain was a giant of the LA session scene in the ’50’s, ’60’s and ’70s playing on countless record and movie dates (he was Henry Mancini’s go-to guitar man). Fender honored the 91-year old earlier this year with a limited release Custom Shop version of the guitar in the picture at left. The axe is called the “Son of a Gunn”, because the original played the memorable guitar line in the theme from “Peter Gunn”. The article is cool, and is in keeping with others I’ve seen from 1987 where the emphasis is on being a professional. Interviewer Jas Obrecht asked Bain “What are the essential skills for a guitarist in your line of work?” The answer is solid gold, and honestly should apply to all guitarists in any band situation:

The magazine started off with a very nice feature about “Tonight Show” guitarist Bob Bain in the opening pages. Bain was a giant of the LA session scene in the ’50’s, ’60’s and ’70s playing on countless record and movie dates (he was Henry Mancini’s go-to guitar man). Fender honored the 91-year old earlier this year with a limited release Custom Shop version of the guitar in the picture at left. The axe is called the “Son of a Gunn”, because the original played the memorable guitar line in the theme from “Peter Gunn”. The article is cool, and is in keeping with others I’ve seen from 1987 where the emphasis is on being a professional. Interviewer Jas Obrecht asked Bain “What are the essential skills for a guitarist in your line of work?” The answer is solid gold, and honestly should apply to all guitarists in any band situation:“You have to know how to play rhythm on an electric guitar without getting in the way or getting a soggy sound. In other words, you don’t sit there playing in 4/4 on a loud electric guitar. You have to find the spots for some fills and occasional solos.”

“I still keep a wah-wah pedal too, because I always play it at the end of the opening theme. We get residuals on these shows, so all I have to do is listen to the first part of the theme and I know if I did the show or not [laughs].

Continuing in the jazz bag, the feature on Freddie Green (“Mr. Rhythm Remembered”) was very well done. Editor Jim Ferguson’s article taught this young jazz fan quite a bit. While my weekly lessons were taught by a master jazz-rock fusion soloist, Freddy Green’s virtuosity came from a different corner of jazz–he was the ultimate accompanist and during his career (which spanned the years 1937-1987) spent with Count Basie was the glue which kept the famous big band together. As Basie once said “he’s the tie-up man of the band”.

Continuing in the jazz bag, the feature on Freddie Green (“Mr. Rhythm Remembered”) was very well done. Editor Jim Ferguson’s article taught this young jazz fan quite a bit. While my weekly lessons were taught by a master jazz-rock fusion soloist, Freddy Green’s virtuosity came from a different corner of jazz–he was the ultimate accompanist and during his career (which spanned the years 1937-1987) spent with Count Basie was the glue which kept the famous big band together. As Basie once said “he’s the tie-up man of the band”. You’ve spent most of your life playing straight-ahead jazz. Do you ever feel confined in this band?

Never…If I want to stretch out and play something outside, Hag doesn’t care. Playing with these guys has really disciplined me because it’s such a big band and each cat usually gets to blow just one chorus. On jazz gigs I could blow endlessly, but with this band you have to be able to make a statement in one chorus. And sometimes it’s much harder to think up something to play on a three chord tune than it is for a tune like “All The Things You Are”, where you have a lot of changes and you can use all those scales and stuff to weave in and out of it. You have a lot more exits in a tune like that than you do on “I’ll Always Be Glad To Take You Back”–C, F and G. If you’re going to play that one, you’d better know the melody.

How do you approach working with Merle’s vocals? Does he give you lots of room?

Basically my goal is to support the soloist or Merle when he’s singing. I don’t do too many fills in concert because you don’t want to run over a guy like Merle Haggard with a lot of meaningless notes. When he starts in on an old Tubb or Lefty tune, generally what I do is just comp some chords….One thing I learned from Roy Nichols is to stay away from the low, muddy end-out of the way of the big, fat piano or steel chords. I’ll stay up in the higher register

What role does Merle’s guitar play in the band?

Merle is a hell of a guitar player. There’s some nights he burns me off the stage. It’s just a bitch, you know, because look at how good he sings already. Damned if he doesn’t come out there and start whippin’ those guitar licks on you. It’s enough to scare a guy! He’s the most damn drivingest rhythm player I’ve ever heard in my life…

How do you approach a solo?

I can’t ever say how I’m going to play because I pretty much go by feel. And, of course, I try to have some concern for the melody….And I know where I’m at by means of the harmonized scale that I learned from Howard [Roberts]…that’s really what I use to keep track of where I’m at. If I’m playing on a B flat blues, for instance, I might play around Fm7 on the I chord. On the IV chord I might play around a B flat m7. And then, say, for the last four bars, where it’s maybe a Cm7 to an F to a B flat, I might use one of those half step things like Cm7, F7, G flat m7, B7 and B flat. I’m approaching it chromatically. You can get to anything chromatically, and that’s a good thing for a young player to learn because it can sure help them out of a lot of situations. I know it did me. You’re never more than one fret away from a good sounding note.

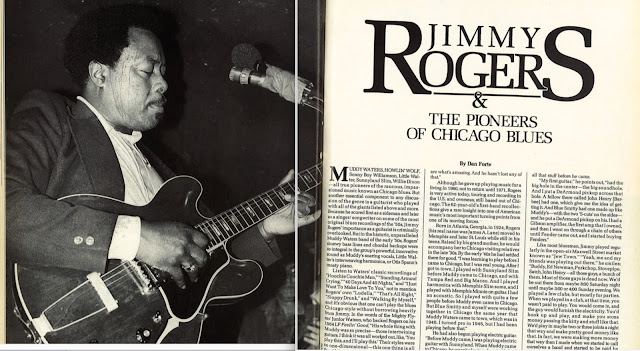

Like most bluesmen, Jimmy played regularly in the open-air Maxwell Street market known as “Jew Town”. “Yeah, me and my friends was playing out there,” he smiles; “Buddy, Ed Newman, Porkchop, Stovepipe, Satch, John Henry–all those guys, a bunch of them. Most of those guys is dead now. We’d be out there from maybe 8:00 Saturday night until maybe 3:00 or 4:00 Sunday evening.

“We played a few clubs, but mostly for parties. When we played in a club, at that time, you wasn’t paid to play. You would come in, and the guy would furnish the electricity. You’d hook up and play and make you some money passing the kitty and stuff like that. We’d play in maybe two or three joints a night that way and make pretty good money…In fact, we were making more money that way than I made when we started to call ourselves a band and be paid by the club owners. When we started playing, we were getting like $8 a night that way apiece–three or four of us–but before that two guys, maybe three would go from one place to another and you’d make maybe $75 or $80 bucks a night on weekends. That was good money. “

Jimmy also had a succession of day jobs, which is how he indirectly hooked up with Muddy Waters. “Off and on I was working days, but I was more interested in playing. The first job I worked on in Chicago was like a packing house–chicken packing in those big 60-gallon drums. Icing them and loading trucks over at South Water Market in Chicago, right off Market St. The next job I had was at Midwest Shoe Manufacturing Company on the West Side. Then I worked at some more packing houses–Liberty, Swift, Armour–and from there I went into construction.

“I was working at a radio cabinet company with Muddy Waters’ cousin Jessie. Jessie would take up with us musicians, like me and Smitty; on weekends he would come around where we’d be playing and he’d buy us whiskey and stuff. He just liked to be with us. So he got me this job at the radio cabinet place where he was working. He told me that he had a cousin that was coming to Chicago. So then I did meet him when he came in, and we got to talking, and he said he was playing down south, down in Clarksdale, Mississippi, for house parties and what have you. And so we just started playing for parties. And from that, club owners hired us. “

Whereas Waters’ main influences on guitar were fellow Mississippians Son House and Robert Johnson, Rogers leaned more towards Big Bill Broonzy, one of the key figures in blues’ transition from rural to urban and already a big star in Chicago. “Big Bill was my favorite guitar man. Year, Bill used to call me his son; I knew him a long time. Tampa Red and Big Bill Broonzy and Big Maceo were really the leading hard blues artists that were in Chicago. And Memphis Minnie, but she was fading. Muddy talked about Robert Johnson, but he didn’t know Robert too well. But he would talk about what he heard about Robert, see. Muddy knew Son House, and Son House was playing along this same style that Robert was playing. And so he picked up a lot of stuff from Son House, this Delta blues player. He had a lot of different stories about those guys back there. But, see, Muddy was, I’d say about 10 years older than I am. So when he got to Chicago, he was like 30 years old.”

Nearly every player who worked in Muddy Waters’ band during the ’50s has since achieved legendary status. In town, the group was intimidating to say the least. “They called us the head-cutters,” Rogers laughs. “Anytime we’d go in a club, man, the other musicians had to back down because we had the floor. If some guy was playing over here, when we’d get of work we’d go to his club–just to have a nice time. But they wouldn’t let us rest until they’d get us up on the bandstand and tear the house up. Then we’d go to the next club.”

Sylvio’s and most of the other South and West Side Chicago clubs were rough-and-tumble joints. “Sometimes the black clubs would be pretty rough,” Rogers allows, “but it never harmed any of us. The Zanzibar was the roughest one–at 13th and Ashland, on the West Side. Just about every week somebody would get messed up. But what could you do? We was pumping the blues good and had a big crowd. Somebody’d look at somebody else’s girl, and there you go.”

Jimmy retired from music in 1960 and didn’t return to active playing until 1971. “My kids were growing up and expenses were going higher. And I was a family man. Music wasn’t doing much for me at the time so I had to do other things. I bought into a cab company with another fellow. Then I left that and had a clothing store….I started back after a while after I got burned out. The store had burned down back when Martin Luther King got killed and I lost a lot. They had a riot in Chicago and they was burning up everything. So I got caught in it real bad. I had to do something. I already had an offer to go to Europe, but I’d refused it. I called back and in a month’s time I was in Europe and that helped me to get myself started again.”

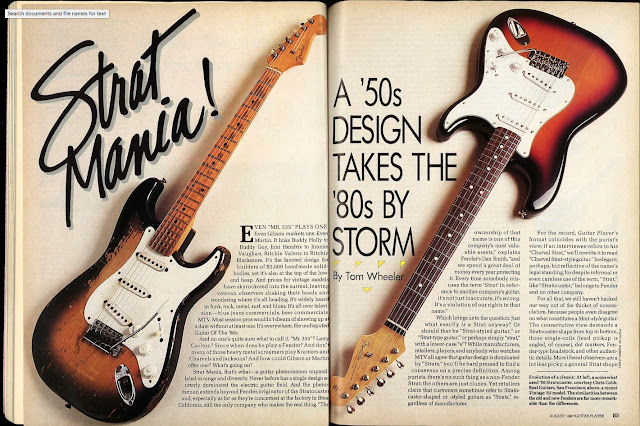

Even “Mr. 335” plays one. Even Gibson markets one. Even Martin. It links Buddy Holly to Buddy Guy, Jimi Hendrix to Jimmie Vaughan, Ritchie Valens to Richie Blackmore. It’s the favored design for builders of the $2,000 handmade solidbodies, yet it’s also at the top of the low-end heap. And prices for vintage models have skyrocketed into the surreal, leaving veteran observers shaking their heads and wondering where it’s all heading. It’s widely heard in funk, rock, metal, surf and blues. It’s all over television–blue jeans commercials, beer commercials, MTV. Most session pros wouldn’t dream of showing up without at least one. It’s everywhere, the undisputed Guitar of the ’80s.

I’ll write more about Strats in the future. While I tend to think that I wasn’t very interested in them at age 17 (preferring Gibson style instruments), they must have had some attraction, because it looks like I clipped out and mailed in an entry to win the Strat giveaway that month!

I’ve already gone on for long enough. I’ll leave you with a Spotify playlist made up of music referred to in the magazine. In addition to the artists mentioned above, there are also some highlights from records reviewed in the back of the issue, as well as some of the Portland, Oregon musicians referred to in an article about the music scene in that town (prior to it’s hipster identification, I guess). I hope you enjoy it. I’ll be back next month, and until then, keep on picking!

Hits: 569

You should seriously blog daily. This is awesome. I love reading this kind of content.