2019

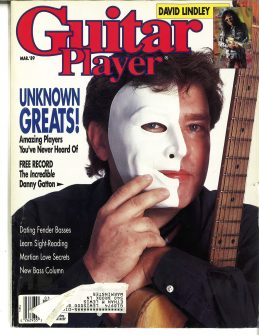

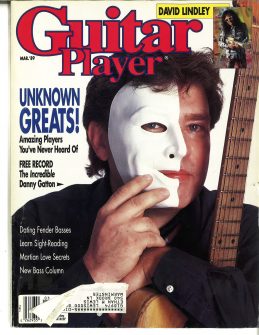

My Back Pages: Thirty Years Ago in Guitar Player (March 1989)

Click here to see all of the previous posts!

In January of 1989 Guitar Player told us who its readers thought were the greatest guitarists (mostly the people featured in the previous year’s issues), but two months later they decided to tell us about guitarists that most people had not yet heard of. This is issue is where I (and most everyone else, I expect) learned about Danny Gatton for the first time. But after re-reading the article, and thinking about him and his life, I wonder if Gatton would have been happier staying “unknown”? Besides the excellent feature on Gatton, this issue didn’t have much going for it. That said, the music referred to in the reviews and articles makes for a great playlist: if you don’t regularly check out the Spotify playlists included in these posts, make sure to look at this one. It might be the only one a beginning guitarist needs to get inspired.

Dan Forte’s article on Danny Gatton was very well written, and the introduction is so evocative! Forte writes of a Gatton show in a Washington D.C. club:

“Before he has even taken a solo, Gatton has most of the crowd convinced that he’s the best R&B rhythm player alive. When he finally does step forward, he shifts from uncanny organ comping to Hammond B-3 licks that would send shivers down the spines of Jimmy Smith, Jimmy McGriff, and Brother Jack McDuff–all with only his ’53 Telecaster, Fender Super Reverb, and a touch of slap-back and tremolo. Next, the crack band jumps into “Mystery Train”, with Danny sounding like the ghost of Cliff Gallup colliding with Les Paul–throwing in a few Earl Scruggs banjo rolls for good measure. On Webb Pierce’s country classic ‘There Stands The Glass’, Gatton alternates James Burton-style chicken pickin’ with ‘pedal steel’ b

ends, deftly combining double-stops and the Tele’s volume knob. Even the well-worn bar-band chestnut ‘Mustang Sally’ gets a new lease on life, with Danny stretching the limits of the soul song while remaining true to its integrity–combining the chops of a Pat Martino with the sensibility of a Steve Cropper, instead of the other way around.

After proclaiming this guy the best country, rockabilly, blues and soul player on the planet, the innocent bystander begins to wonder, ‘Have I stumbled upon simply the best guitarist in the world?'”

I don’t know about you, but 18-year old me was so excited and inspired by that passage, that I remember reading and re-reading the article to learn what I could about a man whose recorded music was unavailable to me at the time (though check out the playlist to hear what would have been had I been able to obtain it in Amherst, Massachusetts). Interestingly, reading it now, when I am older than Gatton was at the time of the interview (and nearly older than he ever lived to be) I sense a kind of weariness and resignation that I’m sure that I never noticed when I was young. At one point Gatton notes “my attention span is fairly short–which is why I change forms of music and tones and attitude. See, I can’t play just one thing and be satisfied.” I’m sure that the ecumenicism of this resonated with me then, but now it just makes me feel sad that Gatton couldn’t derive enough satisfaction from his music (and family and friends and hobbies) to stay with them.

The article includes an interview with Forte, four pages of lessons “in the style of” by Joe Gore, and a special feature on Gatton’s Telecaster, which is where most people first learned of pickup guru Joe Barden. The interview reveals a confident sounding Gatton telling his story, and while it isn’t over-emphasized, what jumps out now is how long and hard Gatton had been working at his craft; he was born in 1945, and got his first guitar at age 9. In other words, at the dawn of rock and roll, when rockabilly was ascendant, and the peak of Les Paul’s fame, Gatton started playing music. Combine an extraordinary gift and constant playing, and the result is—Danny Gatton. Here are a few excerpts from the interview:

Whichever style you’re playing at any given moment, it sounds as though you’ve been doing it forever.

I have–since ’54.

All at once? Or did you go through periods playing strictly country, or R&B, etc.?

Always all at the same time. My first hero was Les Paul. I’d listen to his records when I was a kid, before I ever played, and slow them down to 33 and 16. I was influenced by him, then Hank Thompson, Charlie Christian, and all the big-band records my parents had. My folks liked big-band jazz and western swing, and then other country music too, plus my grandfather and his father were fiddle players, and my father was a guitar player….I took formal lessons from age 9 to maybe 11. Then a friend showed me “Wildwood Flower” one day and I quit my lessons. I said “If I can figure that out, I can figure out whatever else I want to play.” So I was in bands from the time I was 12. We did the Top-40 rock and roll of the day, which are ’50s classics now, and rockabilly when it was in its heyday. I started playing jazz in around ’63, when I first became aware of Wes Montgomery. When the British Invasion hit, that whole thing turned me off, because it was too easy. It was like stepping back. It was easier to play than old rock and roll was. No challenge there. So I started getting into jazz, as a hobby, and playing soul music at night.

At age 13 or so, what sort of tunes could you handle?

I could play a lot of Les Paul tunes, some Jimmy Bryant stuff…

Wait a second! At 13?

[Laughs] I have the tapes. I’ve got a tape of me playing banjo on a tv show, doing “Foggy Mountain Breakdown”….Then the guy interviewed me: “How long you been playing kid?” I said, [imitates high adolescent voice] “Seven months.”

The problem with marketing someone who’s a great, all-around guitarist is, how do you categorize him? If a label wanted you to make a “jazz” or “country” album, would you?

Definitely. I would actually like to make albums where each one focused in one direction.

That question leads off into a longer answer, but I can’t help but think that the angel on Gatton’s shoulder had him hoping this question (and the whole interview) would lead to fame and fortune and a wider audience, while the devil on the other shoulder whispered the dreadful words that caused the unrest to grow in his soul.

This next part always stuck out to me as being almost supernatural :

You never use an electronic tuner to tune up. Do you have perfect pitch?

I don’t have perfect pitch; I’ve got relative pitch. But I can find an E. Sometimes it’s right on, sometimes it’s not. When in doubt, you can use a telephone’s dial tone–it’s almost an F.

What pitch are fluorescent lights?

Between B and B flat–same as the 60 cycle hum when you turn on an electric motor. When I tune, I can always hear the pitch “Honky Tonk” is in–F— or the key of “Mystery Train” [E].

Cool, but it’s really just a trick that comes with experience. I have relative pitch too, and when I tune I can always hear “Misty Mountain Hop”…

Gatton came up playing in the Maryland, Virginia, D.C. area where Roy Buchanan (another genius of the Telecaster, who, despite having a big recording contract and increasing fame, had committed suicide the year before), and it was interesting to me to read about their relationship.

How much influence was going on between you and Buchanan, and in what direction?

I got two things from him–actually three. First, the appreciation of what Telecasters could do. I thought Fenders were basically pretty cheap. I was into fancy Gibsons. Second, those little picks. And then, his tone and approach to the way he played. But he didn’t show me how to do that. I saw him play many times, and he used to sneak into places where I was playing. He’d put on disguises. I’d find Roy sitting over in the corner–“What are you doing here?” “Well, I wanted to see if you played differently when I’m here than you do when I’m not around.”….And he’d call up on the pay phone, and we’d leave the phone off the hook all night long. I’d talk to him on the breaks, then go back to playing, and he’d listen over the phone. He used to come over to my house and try to analyze what kind of a player I was, and we started playing the tune that wound up being “Cajun”. He said, “That’s what you are–you’re a Cajun player.” But he didn’t write that tune; I made it up on the spot in the basement. Meanwhile, Roy was analyzing my playing.

As far as the type of tone and the bending style…

That’s all attributed to him. But he stole it from Albert King, I think. Everybody thinks he invented it, but I don’t think he did. He just heard it somewhere else, just like anybody does.

The only players who cover as wide a range of styles as you are studio musicians such as Tommy Tedesco, who prides himself on being able to play a lot of styles and fake the rest. But you don’t appear to be faking anything.

Oh, I can fake it too. As long as somebody’s laying down the changes, I can play heavy metal, if I want to. That’s how I learned to play most of the stuff–by bullshitting. I didn’t practice to learn how to do these things, I learned them onstage.

…I look at it kind of like this: I’m sort of a curator of guitar styles. And I appreciate Link Wray playing “Rumble” as much as I do Les Paul playing “How High The Moon”, in the same what that an artist could appreciate a rock painting as opposed to a Van Gogh. They’re all art forms, whether they’re crude or advanced, and in order to appreciate them or recreate them, you have to put some study into them to figure out where the person was who did it. And a lot of times you still can’t do it over again the way it was, just because of the way conditions were and how they felt at that time.

The final quote of the interview can be seen as a last grab for the brass ring, with a sense that there will be strings attached:

Since you don’t like the road, and live in the country in southern Maryland, what would you like to see happen with your career?

First of all, I would go out on the road, doing my own thing, if the money was there. But I cannot afford to go out and do it the hard way. I haven’t got the time or energy to go from here to California, playing every bar there is, trying to build up a reputation. Playing in nightclubs for people who don’t know what they’re going to hear, it’s tough.

…[w]e’ve got enough stuff to put out a legitimate jazz record, and almost enough for a straight-ahead country record. It would be real nice to get with a label that would promote it, and I have no problem with going in one direction. If Mr. Record Company and Mr. Producer say “Do that”, I’ll do that. You’ve got to get established in something, I’m finding out. And I’ll manage to sneak some of the licks in, no matter what it is. I may sneak some rockabilly licks into the middle of “Milestones”. I like to play anything, if it’s done right. I’d prefer to play a broad spectrum, but if that’s not possible, I’ll play the game the way it has to be played.

I recently found this interview on YouTube–Gatton talking on late-night TV to Charlie Rose about this issue of Guitar Player, and the jolt it gave Gatton’s career. Check it out:

Pretty neat stuff–at one point, it’s like watching Gatton play just for you, demonstrating various styles of music on his Tele. Rose gets at the topic of the frustration that Gatton must have felt, and Gatton is open about admitting it; he also hints at some self-sabotage. Shortly after this issue, Gatton did get a big record deal with Elektra, and put out some albums, toured the country, and became much better known. But a little over five years after I first read this interview, Gatton committed suicide. I still have trouble listening to his music, because I am haunted by the sadness lurking below the surface.

*****************

That’s it for this month. I’ll be back to discuss the April issue, with a cover story on Metallica, and a fascinating interview with blues legend Johnny Shines. Until then, keep on picking!

*****************

Hits: 839