2019

My Back Pages: Thirty Years Ago in Guitar Player (April 1989)

Click here to see all of the previous posts!

The April, 1989 edition of Guitar Player doesn’t stand out in my memory–I’m sure that I read it, but except for the interview with Miles Davis’ bass player Benny Reitveld I can’t remember the rest.

That said, upon re-reading it for this month’s post, it turns out that there were quite a few very interesting articles. Most impressive to me was the interview with Delta bluesman Johnny Shines, but I also learned a lot about 19th century musician Nicolo Paganini’s relationship with the guitar (and can see some real connections between Paganini and Shines’ erstwhile partner, blues legend Robert Johnson). This issue also features a very good and easy to digest article by Rik Emmett about what is now known as the “CAGED” system, which is a way to think of different fretboard positions. The internet is full of people trying to teach CAGED, and the gist of it was sitting in my bookcase all these decades. Finally, this is a rare issue where all three people featured in the “Spotlight” section are still out there producing music–pretty neat!

That said, upon re-reading it for this month’s post, it turns out that there were quite a few very interesting articles. Most impressive to me was the interview with Delta bluesman Johnny Shines, but I also learned a lot about 19th century musician Nicolo Paganini’s relationship with the guitar (and can see some real connections between Paganini and Shines’ erstwhile partner, blues legend Robert Johnson). This issue also features a very good and easy to digest article by Rik Emmett about what is now known as the “CAGED” system, which is a way to think of different fretboard positions. The internet is full of people trying to teach CAGED, and the gist of it was sitting in my bookcase all these decades. Finally, this is a rare issue where all three people featured in the “Spotlight” section are still out there producing music–pretty neat!

******************

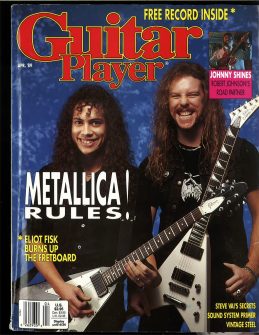

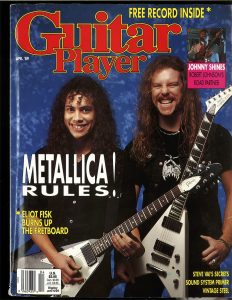

This issue features a very large cover spread on Metallica (such baby faces!) by Joe Gore. It’s ok, but rather long and I wasn’t really a fan of that band then or now. But hidden in the upper right corner of the cover is a small picture of an older African-American man playing a red Gibson ES-345, titled “Johnny Shines: Robert Johnson’s Road Partner”. The interview with Shines is one of the best I’ve seen since I started this blog.

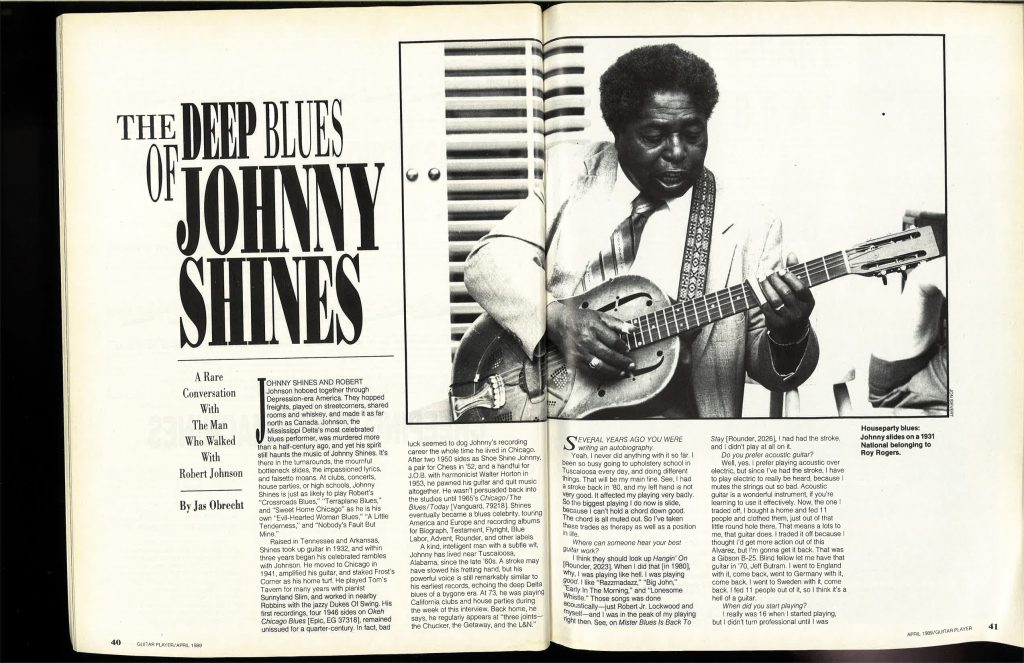

The article is by the always excellent Jas Obrecht and the first paragraph tells us who Shines is:

Johnny Shines and Robert Johnson hoboed together through Depression-era America. They hopped freights, played on streetcorners, shared rooms and whiskey, and made it as far north as Canada. Johnson, the Mississippi Delta’s most celebrated blues performer, was murdered more than a half-century ago, and yet his spirit still haunts the music of Johnny Shines. It’s there in the turnarounds, the mournful bottleneck slides, the impassioned lyrics, and falsetto moans.

Obrecht says that Shines (73 at the time of the interview) took up guitar in 1932 at the age of 16 “and within three years began his celebrated rambles with Johnson. He moved to Chicago in 1941, amplified his guitar, and staked Frost’s Corner as his home turf. He played Tom’s Tavern for many years with pianist Sunnyland Slim….. [i]n 1953 he pawned his guitar and quit music altogether. He wasn’t persuaded back into the studios until 1965’s Chicago/The Blues/Today. Shines eventually became a blues celebrity, touring America and Europe…”

Here are a few excerpts from the interview:

Several years ago you were writing an autobiography.

Yeah. I never did anything with it so far. I been so busy going to upholstery school in Tuscaloosa every day, and doing different things. That will be my main line. See, I had a stroke back in ’80, and my left hand is not very good. It affected my playing very badly. So the biggest playing I do now is slide, because I can’t hold a chord down good….So I’ve taken these trades as therapy as well as a position in life.

Did you ever hear people refer to blues as devil’s music?

Yes I did. When I was a kid, a person heard you singing the blues and recognized your voice, you couldn’t go down their house, around their daughters.

Is that why bluesmen traveled around?

No, they was travelin’ around to make paydays and things like that, with cash money being out.

Guitar strings must have been pretty different back then.

I broke up a lot of guitar strings, because at that time I didn’t know how to play in all the keys. And I had to use a capo to change keys lots of times, so that was hard on a guitar string–wrapping them down, tuning with the clamp on, and pullin’ it. The guitar strings would rattle and break. You could make a capo yourself with a pencil and string. Put the pencil on the neck, wrap the string around it on the back side, pull it up tight. Just as good as any capo.

Did you know many bluesmen back then?

Well, Houston Stackhouse was about the only somebody until I met Robert Johnson through a piano player named M&O.

If you are not a follower of the blues, you may not be aware of Robert Johnson. He is a mysterious figure who is widely regarded as one of the best guitarists ever. He revolutionized Delta blues slide guitar and many people like to speculate that he would have continued on to be kind of a proto-Jimi Hendrix had he not died under mysterious circumstances in 1938 at the age of around 27. I first became aware of Johnson when I read the pulpy but awesome The Hammer of The Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga. That book began with the story of how Johnson went to the crossroads one dark night to sell his soul to the devil to get his musical talent. But more on that later. Back to the interview!

What kind of musician was Robert Johnson?

To me, he was just as great as Charlie Parker. The man did everything. Whatsoever you did on a horn or on a piano, he figured he could do on a guitar, and he did it. And he didn’t look for it, either. I never seen him practice. I never seen him look for nothin’. He’d just sit down, tune a guitar, whatsoever you wanted him to play, he’d play it. Just like we’re sitting here talking now, the radio be playing. Robert heard something on the radio he liked, he never stopped talking with you. Tonight or tomorrow he’d pick up his guitar and play the song, note-for-note, chord-for-chord, word-for-word. He was way before his time. I know he played rock and roll. It was the same beat, but it just wasn’t called rock and roll. I know many chords he never heard of, because he couldn’t read music, but he could just pick up a guitar and make them. He was a genius.

That is super interesting. Certainly, whether it derived from God or the Devil, Johnson seems to have been gifted with perfect pitch and an extraordinary facility with music.

The next few questions really stood out to me. As a former history teacher, I’ve spent decades learning about life in America in the Jim Crow era, and this interview with Johnny Shines really personalizes the precarious nature of life as an itinerant Black musician during the Great Depression. The ever present danger from White law-enforcement and railroad cops must have been a very frightening prospect.

Did you [and Johnson] do much two-guitar music?

No, he didn’t like that. He’d go one way, and I’d go the other. We’d work in the streets. I’d go over here and start playing, and he’d go over there and start playing. He’d draw his gang; I’d draw mine.

How did you travel?

If an empty boxcar was handy, we’d get in it. If it was not, we’d get on it. Ride it until it stops or somebody hit you upside the head [laughs].

What was the first thing you’d do when you hit town?

Just try to find out where the black neighborhood was. Walk up and down the railroad track and just watch to see the black kids. Whichever side we find the black kids on, that’s the side we go, because that was the black side. All the towns was segregated then–whites on one side of the tracks, blacks on the other one. We’d play all day, if the money was still hoppin’, because we didn’t have no particular place to go. As long as there’s nickels and dimes afloat. When they quit, then we’d just walk on.

Do you remember this as a good time of your life?

It was some of the best of the times, because I had to make my own way through my own skills. I felt more freer than at any other time. But now, if I got into a town like tonight-on a Monday night-by Thursday I’d have me a job somewhere. Because at that time the police was bad about picking you up for vagrancy. I always had a job to go to, because the police knew when you went there. Everybody knew everything you did in those small towns. I was dishwashing, busing dishes, doing something to keep the police off me, but I was living off the guitar. I’d get off work in the evening, come and get my guitar, and walk down the street, playing real slow. Somebody go, “Hey! Come over here!” I go, and that’s where we pitched the party at. They’s slip me a dollar that night, and I wasn’t getting that much for a week’s work, $4.75 or something like that.

Were there any places where you did especially well?

St. Louis was a profitable town. Memphis was always good. I’d go down to Handy’s Park, play with the guys down there. Now, a guy over here have a big crowd, and we’d strike up over there and probably pull half his crowd or all of his crowd. If you pull all of his crowd, that’s what we called “headcuttin”–we just cut his head!

Seriously, I think that is some of the most evocative stuff I’ve read about this period. I mean, think of all the scary things that Shines treats as everyday occurrences: illegally riding in or on top of a railroad boxcar (and evading the police who violently beat freeloaders), traveling from town to down, looking for menial work to keep the police at bay, and playing on the street or at house parties for loose change. All with un-amplified, acoustic guitars.

Obrecht turns his questions back to Robert Johnson, and more details about the enigmatic blues legend emerge:

You’ve said that Robert Johnson played polka music on guitar.

Yeah. You had to do it. You see, when I come along playing guitar, lots of times you wake up in the morning and you didn’t have no money at all. Somebody ask you to play a song, maybe they’d give you a dollar for that song. That meant about four meals off of a dollar, ’cause you could get a meal for a quarter or 30 cents. And if you couldn’t play that song, you’d miss that money. So you had to learn to play some of everything you heard. If we passed a white dancing hall and the big bands was playing in there, whatsoever kind of music they was playing, we used to have to listen to. Hide around outside and listen. So we’d go home, and when we get ready, we’d play those same pieces.

So when you were working the streets with Johnson, you only played blues once in a while?

Lots of popular songs in between–whatsoever the people seemed like the enjoyed more. When we played for Polish people, we had to play Polish music. I learned “Beer Barrel Polka”, “Too Fat Polka”, as well as a few Jewish tunes. We had to learn them too.

What were your favorite guitars back then?

I had a little black Regal guitar, and then later on I had a Kalamazoo like Robert had. We both had them. The Kalamazoo was an f-hole Gibson with a flaw in it. He really liked that arch-top. Yeah, had more body to it. Then we bough a flat-top in Steel, Missouri after we lost our guitars in a fire in West Memphis. Robert and I walked out to get some food, and on our way back we looked up and saw this place afire. I said, “Robert, that look like where we live at.” He said, “Yeah, it sure do.” Sure enough, got there, that’s what it was. Hunts Hotel–this black fellow had a little place there, nothing but a rooming house. Paper walls and things like that. Rooming houses ain’t worth a shit. You could fart in your room and deafen the fellow in the other room [laughs].

Was [Johnson] a peaceable person?

Until he started drinking. He started drinking, he’d do any goddanged thing. Wasn’t nothing too good for him to do. At first, he drank corn liquor. When the bonded liquor come in, Ten High and Dixie Dew. Those cheap brands of whiskey. We drank that ’cause that was what was was able to buy. We’d buy a better brand once in a while.

Were you ever much of a drinker?

That’s all I would do. Yeah, I had the habit when I went to bed, I had the habit when I woke up, I had the habit when I got up. That was pretty well all through my life, but younger some.

Did you sense that he was going to have a short life?

No, I never did. It was just very hard when I heard he was dead. I just couldn’t believe it. Honeyboy Edwards was the one who confirmed it with me that he was dead.. See, Sonny Boy [Rice Miller] said Robert died in his arms, but Sonny Boy was such a big liar. He speaked lying lies. Still couldn’t believe that Robert was dead. Since I made my comeback, I look any day to walk up on Robert, or Robert walk up on me. I feel his presence many times.

The interview goes on to talk about Shine’s experiences living and playing in Chicago alongside people like Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon. Some really great stuff. The last excerpt I want to share is where Johnny Shines describes the blues.

Do you consider yourself a Delta bluesman?

That’s what I am, a Delta bluesman. And now, I’m considered the king of the Delta blues. But what we call the Delta blues is not blues, it’s storytelling music. It’s something that has happened in somebody’s life that they are telling a story about. For instance, I walk up to you as you was fixing to catch a bus and go to work. I tell you, “My house burned down last night and burnt up three of my children.” You say, “Yes, I’ll listen to you later. Say, here comes my bus, I’ll see you.” You get on your bus and go. But now, tonight, when I put music to it, you pay $10 to hear me tell you the same story I tried to tell you for free at the bus stop. Same story!

You see, blues don’t have no race. Blues don’t have no level. Blues is just like death. Everybody is going to have the blues. If they haven’t already had them, they’re gonna have ’em. Because everybody is going to have some bad luck in their life. They are going to be confronted with fortunes unexpected–one way or the other. The blues i only a though anyway. You see, whatsoever touches the heart is where the blues come from. Say, a man wins $15,000 or $20,000 at the racetrack. Well, he’ll have a happy blues, because he’s happy from the heart on out. And the man go out there and lose all his money–his wife has told him she gonna quit him if he lose his money again–he got a different blues [laughs].

As you can probably tell, I loved this article. I just can’t stop thinking about all of the details and insights. I’m so glad that GP made such an effort to interview so many old bluesmen before they passed away–what a valuable oral history contribution. Way to go, Guitar Player!

*****************

As I mentioned, Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga was one of my favorite books. In fact, in the fall of 1988 it was one of the foundational texts for the band I joined at college. In the opening chapter, before expounding on his thesis that Led Zeppelin (or at least, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and John Bonham) had struck a deal with the Devil for their success, author Stephen Davis tells the story of two other legendary musicians who may have done the same. You’ve already learned about Robert Johnson, but the other was the Italian violinist/guitarist/composer Nicolo Paganini. According to my well-worn copy of HOTG:

As I mentioned, Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga was one of my favorite books. In fact, in the fall of 1988 it was one of the foundational texts for the band I joined at college. In the opening chapter, before expounding on his thesis that Led Zeppelin (or at least, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and John Bonham) had struck a deal with the Devil for their success, author Stephen Davis tells the story of two other legendary musicians who may have done the same. You’ve already learned about Robert Johnson, but the other was the Italian violinist/guitarist/composer Nicolo Paganini. According to my well-worn copy of HOTG:

“Consider the life of the Genoese violinist Nicolo Paganini (1782-1840)…. Paganini was the first great virtuoso and superstar within modern memory…..Appearing at sold-out concerts in tight pants and very long hair, he caused women to scream and faint as he produced mysterious effects on the violin….”

“…His fame was so wide and his power over his instrument and women so legendary that every European peasant knew for a fact that Nicolo Paganini had sold his soul to the Devil….In one contemporary account, Paganini ‘secured his mastery over mankind and his pre-eminence in his art from the devil in exchange for a soul already sufficiently blasted and damned.’…And when Paganini died in France in 1840, the Catholic church denied him burial in consecrated ground, despite pleas from Rome, because local peasants were too frightened.”

There is very little in Davis’ book that is demonstrably true, but it is incredibly fun to read. I know that I thrilled to this section back in the day, and I still like it. Well, this little-remembered issue of Guitar Player featured a short article called “Paganini and the Guitar” by Leslie Shepard, author of a biography of the famous musician. Shepard quotes several 19th century sources to show that the guitar and mandolin were as important to Paganini as the violin:

“…Indeed, the great violinist Karol Lipinski said in all seriousness that he was unable to decide whether it was the violin or guitar that Paganini played best.

According to the 19th century violin authority George Dubourg, ‘To those early days belongs the fact of Paganini’s transient passion for the guitar, or rather for a certain fair Tuscan lady, who incited him to the study of that feebler instrument of which she was herself a votary. Applying his acute powers to the extension of its resources, he soon made the guitar an object of astonishment to his fair friend, nor did he resume in earnest that peculiar symbol of his greatness, the violin, till after a lapse of nearly three years.'”

Was this the first example of playing guitar to attract women? In all seriousness, apparently Dubourg was discussing “The Lost Years” of 1801-04 when Paganini withdrew from public performances, “living in quiet seclusion with a wealthy Tuscan lady of rank, whose identity he loyally never divulged…”

Shepard quotes guitarist Ferdinando Carulli (1770-1841) a contemporary of Paganini to show that the latter composed accompaniments for all of his violin concertos on guitar: “…Paganini was a fine performer on the guitar, and…composed most of his airs on this instrument, arranging and amplifying them on the violin according to his fancy.” Shepard also discusses several prominent aspects of Paganini’s violin technique (especially pizzicato) that can also be played on guitar.

Shepard quotes guitarist Ferdinando Carulli (1770-1841) a contemporary of Paganini to show that the latter composed accompaniments for all of his violin concertos on guitar: “…Paganini was a fine performer on the guitar, and…composed most of his airs on this instrument, arranging and amplifying them on the violin according to his fancy.” Shepard also discusses several prominent aspects of Paganini’s violin technique (especially pizzicato) that can also be played on guitar.

Reading this article right after reading the Johnny Shines article reveals some wonderful similarities between Paganini and the itinerant bluesman and his colleague Robert Johnson. Of course, Paganini did not have to worry about racial prejudice and laws designed to make him a second-class citizen, but tell me that these stories don’t sound like they could be part of Shines’ tales:

…An Italian writer described how he encountered Paganini, whom he had seen on previous occasions without knowing who he was. ‘Just as the stars began their first scintillations, I sat down to rest under the Loggio degli Uffizi. A joyous party passed and sat down on a marble seat some distance from me; soon after, celestial sounds struck upon my ear, by turns joyful and plaintive, evidently produced by the hand of a superior artist.’

‘Silence succeeded the hilarious shouts of the merry party, all of who seemed as transfixed by the divine music as myself. They all rose silently to follow the artist, who continued walking as he played. I also followed to discover what instrument it was I heard and who the artist might be that discoursed so enchantingly upon it. Arriving at the square of Palazzo Vecchio, the party entered a restaurant. There they regained their former merriment, and the leader more than his companions displayed extra-ordinary animation. To my great surprise, the instrument was a guitar (which seemed to have become magical) and the performer I discovered to be the stranger I had so repeatedly met. He was no longer the suffering being he had seemed; his eyes sparkled, his cravat was loosened, and his gesticulations, those of a madman. I inquired his name of one of the party.’

‘”None of us knows it!” replied the individual to whom I addressed myself. “I was in company with my friends who were singing and dancing to my guitar, when this singular man pushed in among us, and snatching the guitar from my hands, commenced playing without saying a word. Annoyed at the intrusion, we were about to lay hands on him, but without noticing us in the least, he continued to play, subjugating us to his exquisite performance….”

‘Some days later, Paganini was announced to give a concert. Eager to hear the incomparable artist whose fame was so universal, I went to the theatre which was crowded to suffocation. At last, the artist appeared–it was the mysterious stranger!”

I really want to learn more about Paganini now. And these 19th century anecdotes are so charming!

*****************

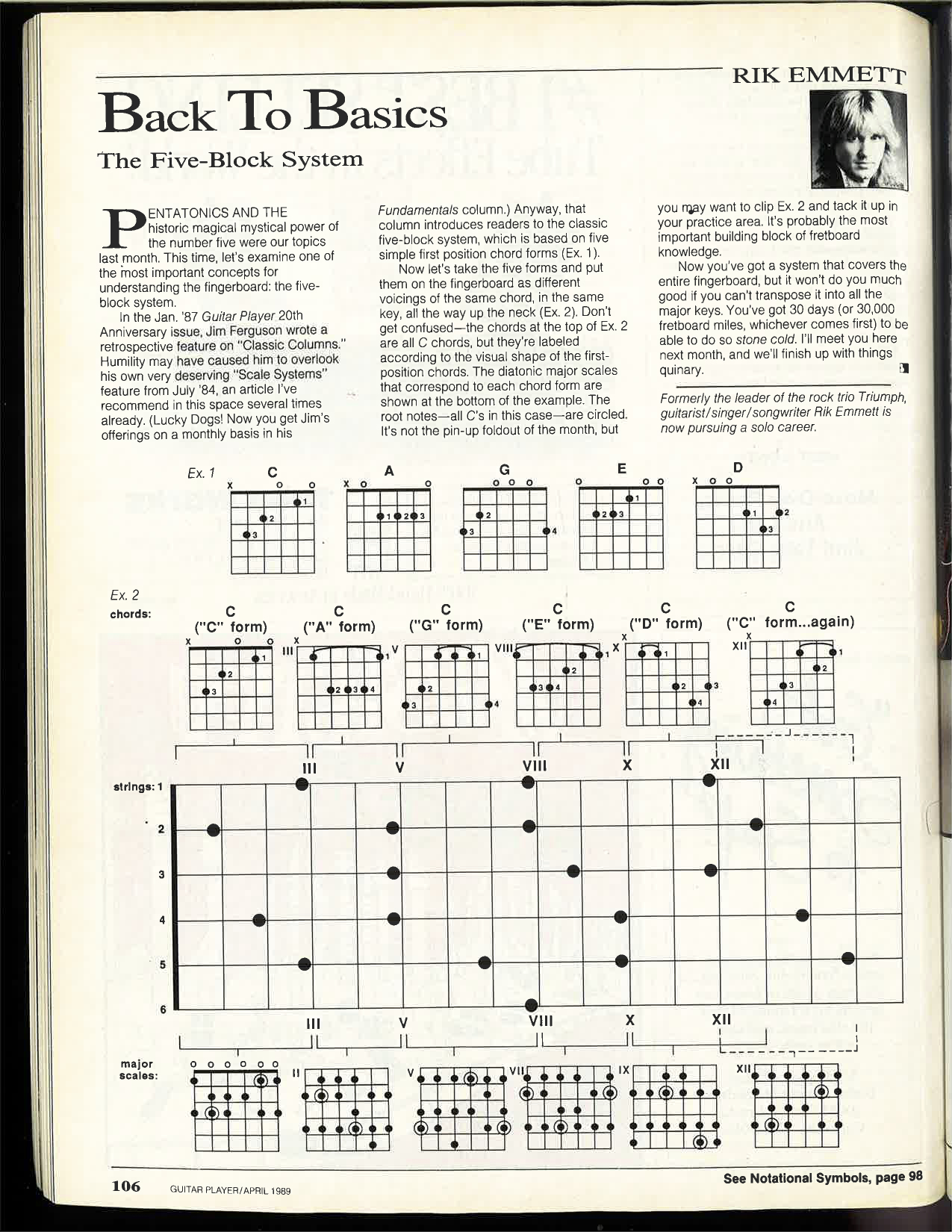

This month’s lesson from Rik Emmett’s “Back to Basics” (always one of my favorite parts of the magazine and still impressive for how well-written and helpful they are) is called “The Five Block System”. Nowadays, people refer to it as CAGED, referring to the way that if one learns the common, open position shapes for the C, A, G, E and D major scales, one can apply those shapes up and down the neck to open up the fretboard. Google “caged system” and you will find hundreds of thousands of results, some favorable, some opposed, all of which discuss this approach to learning the notes on the guitar. I am not a devotee, but I definitely play triads up and down the neck utilizing the familiar open shapes. Anyway, I really liked Emmet’s article when I re-read it, and I do kind of wish that I’d fully absorbed his message thirty years ago–it would have helped for sure!

*****************

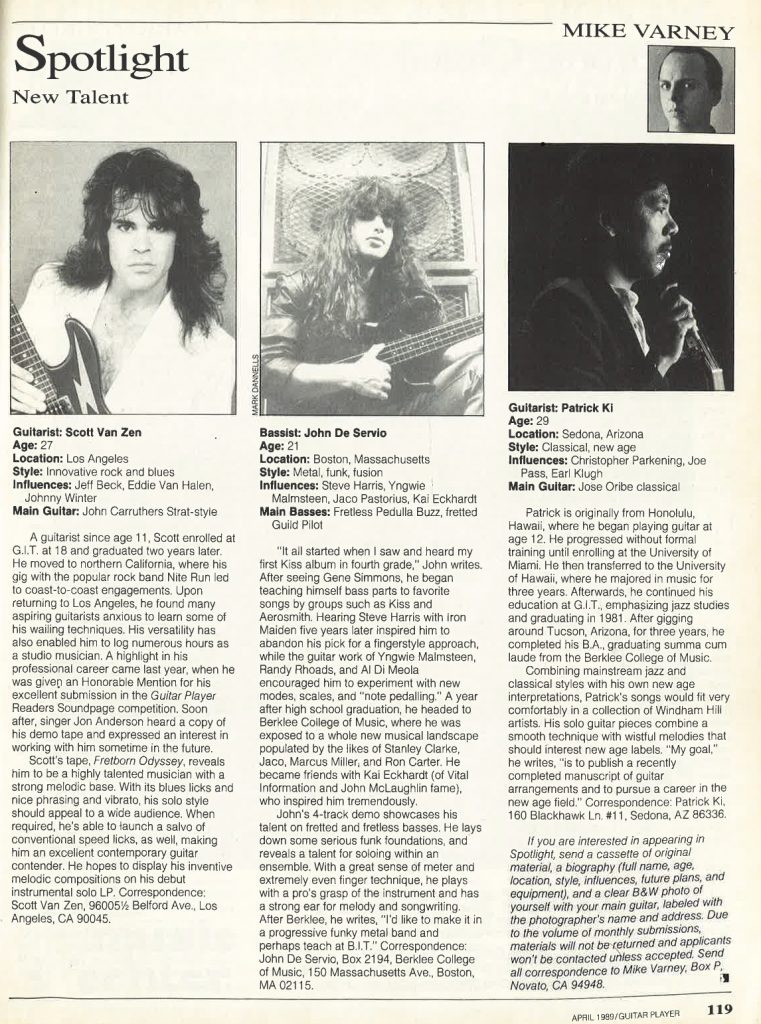

Finally for this month, the Spotlight trifecta! All three of the musicians featured (left handed guitarist Scott Van Zen, bassist John De Servio, and classical player Patrick Ki) have all gone on to have good careers in music, with De Servio playing in Zakk Wylde’s band for decades. Pretty cool to see them here, in their early days!

*****************

That’s it for this month. Unfortunately I don’t seem to have the May, 1989 issue, so I’ll see you in June. Until then, keep on picking!

*****************

Hits: 603