2019

My Back Pages: Thirty Years Ago in Guitar Player (June 1989)

Click here to see all of the previous posts!

The June, 1989 edition of Guitar Player is an interesting one to revisit: on the one hand, the issue devotes 25 pages to a comprehensive look at the state of the art in digital signal processors. This might have been a valuable service to readers back in the day, but nobody would seek out one of these beasts nowadays; while it’s nice to read about the $1300 Korg A3, I can probably do more with my cell phone now for free. On the other hand, the magazine has great interviews with Larry Carlton and Carl Perkins as well as an interesting editorial about fretted instrument imports and exports that led me down a pretty neat rabbit hole doing some research for this post.

******************

The opening editorial from publisher Jim Crockett was titled “The Balance of Payments”, and it discussed the 1988 statistics on imports and exports of acoustic and electric guitars. According to Crockett:

The opening editorial from publisher Jim Crockett was titled “The Balance of Payments”, and it discussed the 1988 statistics on imports and exports of acoustic and electric guitars. According to Crockett:

“…in 1988, about 611,400 acoustic guitars worth less than $100 each were imported into the U.S….And where did most of these come from? Not Japan, as some of you might assume, but from Korea, Taiwan and (ready?) China. In the area of over-$100 acoustics, the United States brought in a little over 41,000 instruments last year, most of those from just Korea and Taiwan.

How about electrics? In ’88, about 485,200 units were shipped into the U.S. Again, mostly Asian in origin. Altogether, America imported about 1,137,700 acoustic and electric guitars–up 167,500 from 1987.

In 1988, while Americans were importing 652,000 acoustic guitars, we were exporting just 29,600. Talk about your ‘imbalance’. And at the same time we were welcoming 485,200 foreign electric guitars, we sent out only 33,500.

Overall, America brought in 1,137,700 or so guitars, but exported merely 63,100. “

Well, there is a lot to unpack here, even beyond the fact that this simplistic analysis sounds like the kind of thing that around this same time led a somewhat well-known real estate mogul in New York to decide that “America was losing”. First of all, it sounds about right to me that guitar sales were increasing at this time, which was the peak of rock on MTV, with guitar solos on every pop song and grunge just a disquieting rumble in the distance. Second, I wish that Crockett had been able to give us dollar values of the imports and exports. Finally, I wonder what the numbers are like now, when so many people are proclaiming the end of the guitar (despite a seemingly endless supply of cheap guitars on Amazon and eBay).

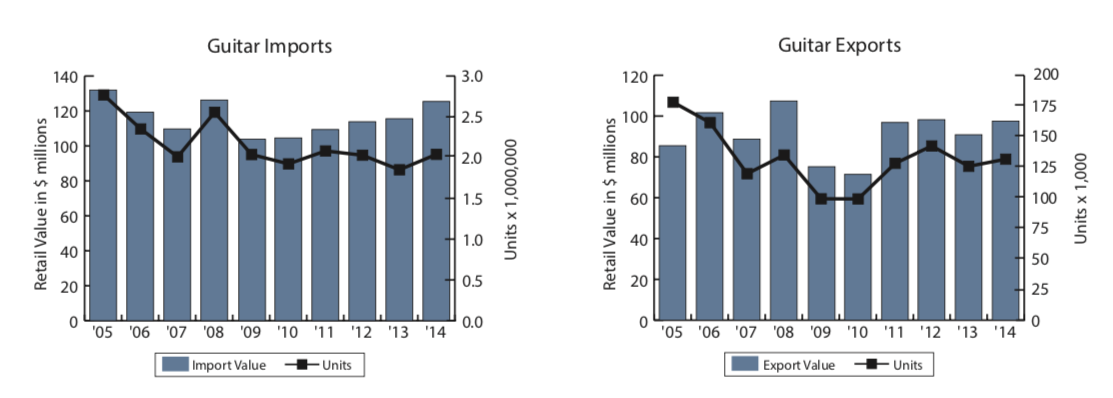

Fortunately, I didn’t have too far to look. The 2015 NAMM Global Report is available online, and it is full of fascinating details, including these charts:

In other words, in 2014 (26 years after Crockett’s data), the United States imported 2 million guitars and exported just over 125,000. Both of these numbers are increases over the 1988 totals, but, interestingly are down quite a bit from 2005 before the Great Recession (and before the spread of smartphones). Now of course the U.S. population in 1990 was just under 249 million and by 2010 was over 310 million, so one could assume that the population increase alone should result in more guitarists, but I can’t do that kind of math. The report does say that:

“Acoustic guitars were the top performers in 2014. A 10% increase to 1,498,700 units translated into a 12.5% gain in retail value as customers opted for higher priced instruments. It’s difficult to pinpoint a single catalyst for the improvement. Retailers and manufacturers interviewed cited a better economic climate; the rise of singer-songwriters like Taylor Swift, who have attracted more female buyers, and consumers looking for an antidote to an increasingly digitized world.

In the realm of electric guitars, unit volume edged up 2% to 1,132,250, while estimated retail value increased 8.3% to $505.9 million. The shift to higher-priced products was generally welcomed by manufacturers and retailers….[h]owever, some still expressed concerns. ‘We’re seeing fewer first-time buyers and a lot more older guys adding instruments to their collection.'”

Interesting stuff, at least to me. And I can’t help but wonder where all these guitars are going. I mean, they aren’t disposable. A glance at Reverb as I write this on June 20th shows 131,550 used guitars available on the site, including 6,128 from the 1980’s–some of which might be the ones Crockett was talking about. So in some ways, this is probably a great time to be a guitar player due to the saturated market; I mean, you don’t have to look far or pay much for a guitar these days which makes it great for beginners and “collectors” alike. What do you think about this?

*****************

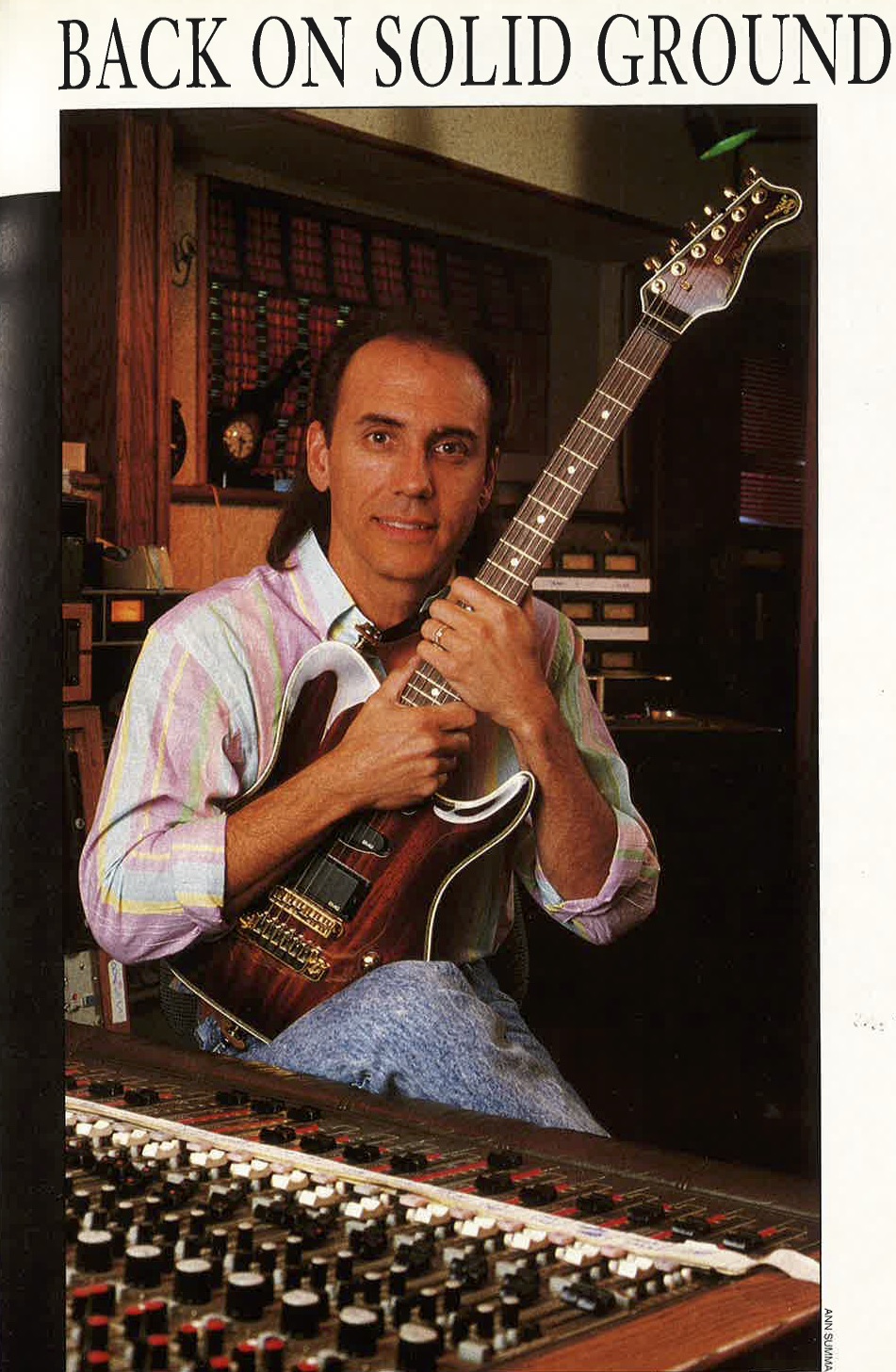

One of the guitarists that my teacher, Jim McCarthy hipped me to was Larry Carlton, the studio legend who contributed to so many Steely Dan, Crusaders and other records in the 70s and 80s. As I’ve mentioned in a previous post, Jim was in the audience at the Baked Potato club in LA (where he was getting his degree at the Guitar Institute of Technology) when Carlton recorded his 1986 live record Last Night, which you can hear in the playlist below. In June of 1989, “Mr. 335” was promoting his new LP On Solid Ground and also making a remarkable comeback from a near-fatal shooting during a home invasion the year before.

Larry Carlton is an amazing musician and a very humble person (to me, the best interviews in Guitar Player are with the people who exhibit the most humility) and it’s worth your while to check out some interviews with him online. This interview was largely nuts and bolts on the making of On Solid Ground, which to my ears sounds terribly dated (I had it when it came out and really dug it, but the sound is just way too “80’s” for me now. But at the end there is a quote from Carlton that I think every musician, heck, every creative person should take to heart:

“Before we go, there’s something I’d like to say to other guitarists. I just turned 41 this March and my philosophy is staying consistent in that there’s really no road in my mind for competitiveness and pettiness between musicians. It’s so important that we just want the best for each other. There are guitarists who play wonderfully and entirely different from the way I play, and it doesn’t mean they are better or I’m better. None of that matters. The idea is that there are guys out there trying to make great music from their hearts, and we just need to support each other.”

I think that’s just great. Earlier in the interview, when Jas Obrecht asked Carlton why his music was so “strikingly positive”, the guitarist said:

“When you have to stare at reality, you get to make a choice: Is this going to be a real negative event in my life, or is it going to be a positive thing? And I choose to make it a positive thing. That’s not to say that I don’t daily live with the frustrations of my voice [he was shot in the neck and his speech was affected]. It’s a drag, man, not to have full use of all your capacities, but it could have been so much worse….I could have been nothing.”

Those are also pretty powerful words. It’s easy to talk about “perspective” and such, but I think it’s remarkable that someone who was the victim of such random violence was able to speak so positively so soon after the fact.

*****************

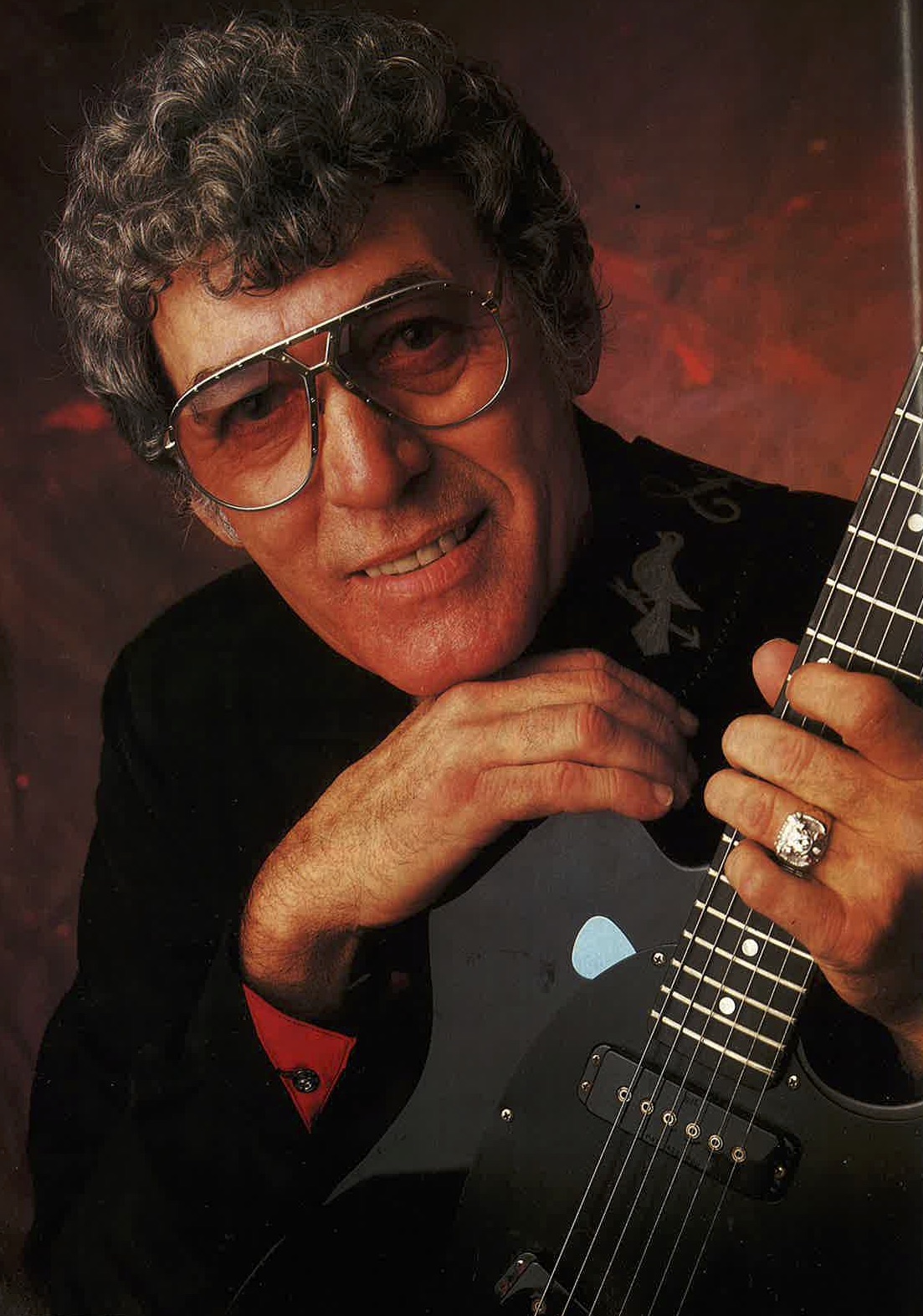

I love rockabilly music and Carl Perkins has always been one of my favorites. I remember reading this interview with Jon Sievert and being struck by the many tragedies and setbacks that he overcame (or at least, lived through) in his career. The man who wrote (or popularized) such classic songs as “Blue Suede Shoes”, “Matchbox”, “Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby”, “Put Your Cat Clothes On”, and “Honey Don’t” was a peer of Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley at Sun Records in Memphis in the early 1950’s, but a near-fatal car crash derailed his career early in 1956, then his brother (and bandmate) died of cancer, then Perkins accidentally got his hand caught in an electric fan and mangled his hand. In the mid 1960’s he accidentally shot himself hunting and at that time his drinking began to get problematic. Johnny Cash hired Perkins as a member of his band and perennial opening act which helped Carl get back on his feet. At the time of this article, he was promoting a new solo album as well as a great, all-star tribute on Cinemax, which you can (and should) see here:

I love rockabilly music and Carl Perkins has always been one of my favorites. I remember reading this interview with Jon Sievert and being struck by the many tragedies and setbacks that he overcame (or at least, lived through) in his career. The man who wrote (or popularized) such classic songs as “Blue Suede Shoes”, “Matchbox”, “Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby”, “Put Your Cat Clothes On”, and “Honey Don’t” was a peer of Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley at Sun Records in Memphis in the early 1950’s, but a near-fatal car crash derailed his career early in 1956, then his brother (and bandmate) died of cancer, then Perkins accidentally got his hand caught in an electric fan and mangled his hand. In the mid 1960’s he accidentally shot himself hunting and at that time his drinking began to get problematic. Johnny Cash hired Perkins as a member of his band and perennial opening act which helped Carl get back on his feet. At the time of this article, he was promoting a new solo album as well as a great, all-star tribute on Cinemax, which you can (and should) see here:

Watching how Perkins interacts with such well-known disciples as George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Dave Edmunds, Roseanne Cash and Eric Clapton gives an insight into his humility (there’s that word again) and modesty and it comes through even more in this interview. As Sievert notes “Perkins is a warm, gracious man without a trace of bitterness about what might have been.” I find that so admirable, and something I struggle to achieve in my own life. At the time of this article, Perkins was 57 and eager to make a new start on his much-stalled career; unfortunately he died only 9 years later after suffering a series of strokes. Here are some excerpts from the interview that I found interesting:

Did you always record your guitar and vocals at the same time at Sun?

Yes, that’s the way I love to do it, and I think it’s time to really go after nailing the simplicity of the rhythm and that old, raw, unrehearsed guitar sound. I enjoy listening to a dude play himself into a hole. Sometimes working your way out of unknown areas on the guitar will produce some interesting things.

Can you recall some instances when this happened to you?

Everything I cut at Sun Records, I started digging myself a hole in the kick-off and stayed pretty well in that hole all the way through. Really. It was not a rehearsed thing. It was, for the most part, a spontaneous thing happening among a four-piece band. Things like “Matchbox” with Jerry Lee Lewis on piano. I didn’t have an opening or anything. I started with that rhythm riff, and Jerry Lee said “Yeah, I like that man.” So, Jerry started hitting the piano along with the guitar, and it just set up a little thing. I knew a line or two from an old blues song I’d heard in the cotton fields when I was a youngster, and the song “Matchbox” just happened.

We never went in there with that sound or with that way of recording. I think that if there’s anything good to be remembered about most of the old Sun records–and I include Elvis’–it was the fact that it wasn’t rehearsed. There weren’t any outstanding musicians. It was everybody playing a feel and just getting in the groove and really enjoying it. It was music that was born at the time right there. Those days are long gone. Now it’s a three-hour session and you better be ready. Back then, it could go three days, or as long as the jug stayed about half full. For that reason there were some licks that came out of there simply because a guy got up on the neck and he knew in his soul “Whew, I gotta work my way back to where I usually play. I’m way down in here.” And on the way back out, sometimes there’d be a hoss of a little lick. For Scotty Moore, Roland Janes and most guys at Sun, that type of thing would happen.”

Perkins goes on to describe rockabilly as “a more ragged-edged country sound. I always thought it was a white man’s lyric to a black man’s rhythm.” He came to this perspective honestly through his upbringing–growing up in Tennessee, Perkins’ family were the only white sharecroppers on a cotton plantation. In the interview he described his early days with the guitar:

Could you talk a bit about how you learned to play?

I was about four or five. On the Sunday before I started school, I cried all day. I remember hearing my mother telling my daddy, “Buck, I believe he doesn’t want to leave his guitar at home.” The first time I climbed on the school bus, I stepped up in there with an old, beat-up guitar, and every kid was looking and wondering. I didn’t want to spend a day without it. I loved guitars, and that’s never gone away.

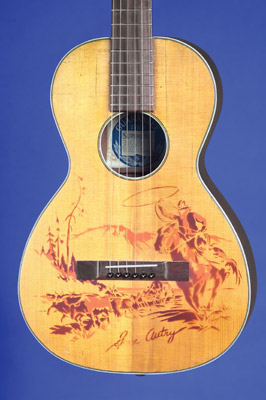

Do you remember what kind of guitar you took to school?

It was a Gene Autry model, with a picture of him and his horse painted on there. The strings were about an inch over the fretboard. Mama had one big comb that we all combed our hair with, and the big teeth in that comb made a nice little old pick. Most of the combs my poor mama had back in those days had just the little teeth in them. I’d break me out a couple of the big ones and put ’em in my shirt pocket for spares.

Was there anybody around to teach you the basics of the guitar?

My daddy knew C, G and D and that was about it. Oh, he had what he called an off-chord–an A–that he would throw into a few songs. And there was an old black man named John Westbrook who sharecropped the same land we did. Uncle John had a little guitar that looked a little better than mine–the neck wasn’t warped as bad. But he just really knocked me out because he had a chord called E. It had such a beautiful tone: you know, the bass string open and the bottom two open. It was a pretty easy chord to make down there on that 1st fret and he could slide down and go [sings sliding sound]. Whoa, me. Quickly the simple country got put on the back burner in my little soul. I though that little blues lick was the greatest sound I ever heard in my life. I though he was the greatest guitar player who ever lived. As I got older, I realized he wasn’t an accomplished player, but he just moved me to the bone.

That’s the most important thing.

That’s exactly right! It’s like today, boys like Eric Clapton and George Harrison say, “If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have gotten into this business.” And I say, Man, I don’t want to hear about none of my old simple licks in what you all do. They’re great guitar players and play so much more than I ever dreamed of playing. But maybe, just maybe, it was that little old basic string-pushing thing that came off the fingers of that old black man and into my simple country soul that got them. I twisted them around and got them working as up-tempo country songs, but that’s what some of these boys heard, and in some little way, he affected them as he affected me. Clapton told me, “Man, that lick on ‘Matchbox’ just hooked me, I decided then that’s what I wanted to play.” It’s a humbling thing when these people say that, and yet it takes me back to how Uncle John affected me. He was old and tired, but he took the time with that little white boy. He said, “That guitar can take you miles away from these cotton fields, boy, if you work on it.” He died just a few years after I started playing, but his memory will be strong forever in my life. The black man loved the little white boy and shared his blues with him. There’s something awesome in that.

I don’t know about you, but I find that story and Perkins’ dedication to John Westbrook’s memory to be very moving. Of course as Perkins’ career progressed, he moved in the same circles as all of the other rock and roll pioneers, black and white. He had two really good anecdotes about conversations with Chuck Berry and Fats Domino:

It seems like you and Chuck Berry had a lot in common, because only a few guys on that early rock scene sang, played guitar, and wrote songs.

That’s true. When I first heard “Maybellene”, I could hear some three-chord country in it. We talked about that in the early days. I remember him saying “I thought you were one of us when I heard them “Shoes”. I said, “Well, I sure heard some Bill Monroe in ‘Maybellene’, and he said “You’d better know it.”

Did you ever think that you were sort of two sides of the same coin? You’re white and he’s black, but you were both doing the same kind of thing that mixed elements of both.

That’s true, Black was born from white and white was born from black. I remember Fats Domino telling me one night, “Carl, you know music might have done more to do away with segregation than Washington D.C. did.” People in all-white honky tonks in the South didn’t walk up to that Wurlitzer and drop a nickel in there and read “Blueberry Hill-Fats Domino-Black” and “Blue Suede Shoes”-Carl Perkins-White”. It was music and it mixed before people did. Something eased barriers, and pretty soon white teenyboppers were dancing to Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Fats Domino, and it didn’t make any difference.

Great stuff. I love how re-reading these old issues gives me the chance to get these insights from people from the early days of rock and blues. And I can totally picture Chuck Berry slyly saying that he thought Perkins sounded black on his first hit. It never ceases to amaze me that when Perkins was describing his time at Sun, he was talking about something that happened thirty-some years earlier; at the time it seemed “old” to me, but it really wasn’t. But now that so few people from that time survive, reading their memories and stories is a very valuable window on a part of the past to which I owe so much.

*****************

That’s it for this month. The music selection isn’t as good as it has been in the past, but there are some nuggets if you dig in. The July ’89 issue with Jennifer Batten on the cover also has a good interview with Al Anderson of NRBQ and a tour of the Paul Reed Smith factory which should interest the dentists in the audience. Until then, keep on picking!

*****************

Hits: 418